Merthyr’s lords of the ring

MERTHYR is a town with boxing in its DNA.

An extract from ‘The Early History of Boxing in Wales’ on the Wikipedia website may offer an insight into why Merthyr has played such a significant role in Welsh boxing over the years:

‘The opening of the South Wales valleys to industrialisation in the mid-1800s saw a large influx of commercial immigration.

‘This was followed by an improved transport network, which in turn allowed larger crowds, and larger wagers, to be brought to the sport of boxing. When the Taff Vale Railway was extended to Merthyr Tydfil in 1840, the locals celebrated by a contest between Cyfarthfa champion John Nash, and Merthyr hardman Shoni Sguborfawr.

‘The adoption of boxing as a sport for the underprivileged in industrial Wales is compared, by Welsh historian Gareth Williams, to the living conditions of the emerging towns themselves.

‘Towns like Merthyr, one of the heartlands of the world’s iron industry, with its dire health and living conditions, along with a high rate of industrial injury and death, reinforced in the minds of the working class that life was short and brutal.

‘The sport of boxing, though exploitative of the common man, was still a means to rise above the poverty of everyday life and glamourized the primitive.’

100 Welsh Heroes was an opinion poll run in Wales as a response to the BBC’s 100 Greatest Britons poll of 2002. It was carried out mainly on the internet, starting on September 8, 2003, and finishing on February 23, 2004. The results were announced on March 1 (St David’s Day), 2004, and subsequently published in a book.

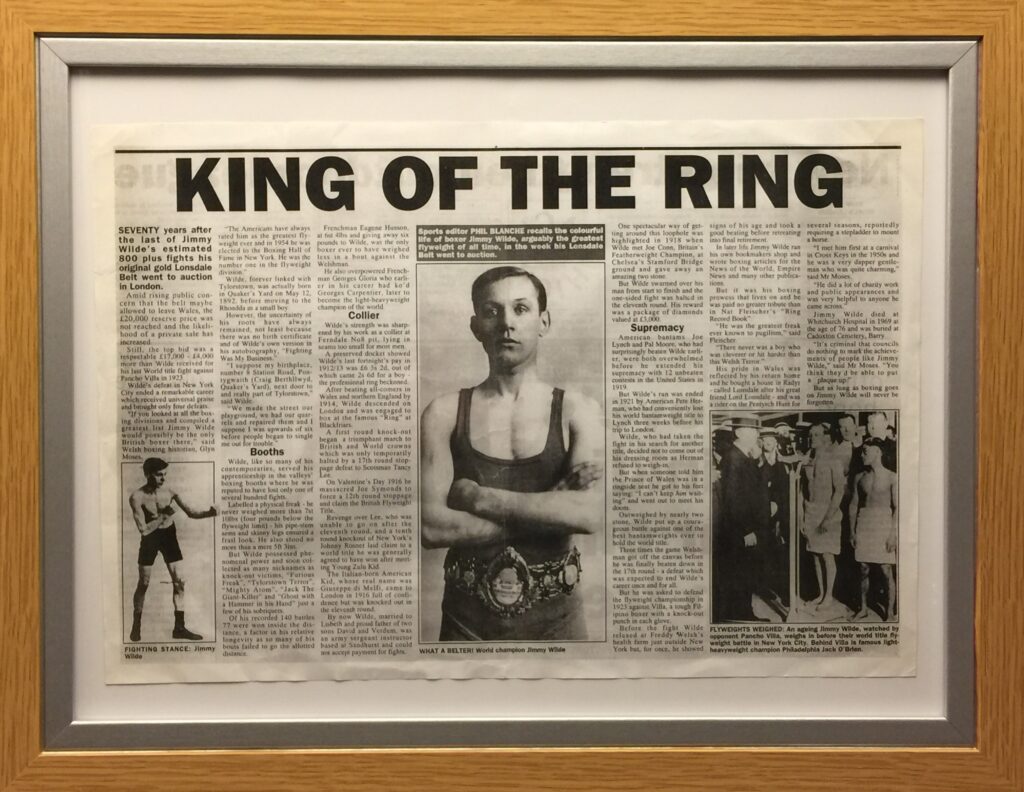

At No 38 on that list, sandwiched between kings, war heroes, bishops, princes, poets and politicans is the diminutive Jimmy Wilde, a humble boxer from Quaker’s Yard, Merthyr Tydfil.

Wilde, born May 15, 1892, was a Welsh professional boxer and world boxing champion, often regarded as the greatest British fighter of all time.

Wilde earned various nicknames such as ‘The Mighty Atom’, ‘Ghost with the Hammer in His Hand’ and ‘The Tylorstown Terror’ due to his bludgeoning punching power.

While reigning as the world’s greatest flyweight, Wilde would take on bantamweights and even featherweights, and knock them out.

As well as his professional career, Wilde participated in 151 bouts judged as ‘newspaper decisions’; of these, he boxed 70 rounds, won seven and lost one, with 143 being declared as ‘no decisions’. Wilde has the longest recorded unbeaten streak in boxing history, having gone 104-0.

He was the first official world flyweight champion and was rated by American boxing writer Nat Fleischer, as well as many other professionals and fans including former boxer, trainer, manager and promoter Charley ‘Broadway’ Rose, as “the Greatest Flyweight Boxer Ever”.

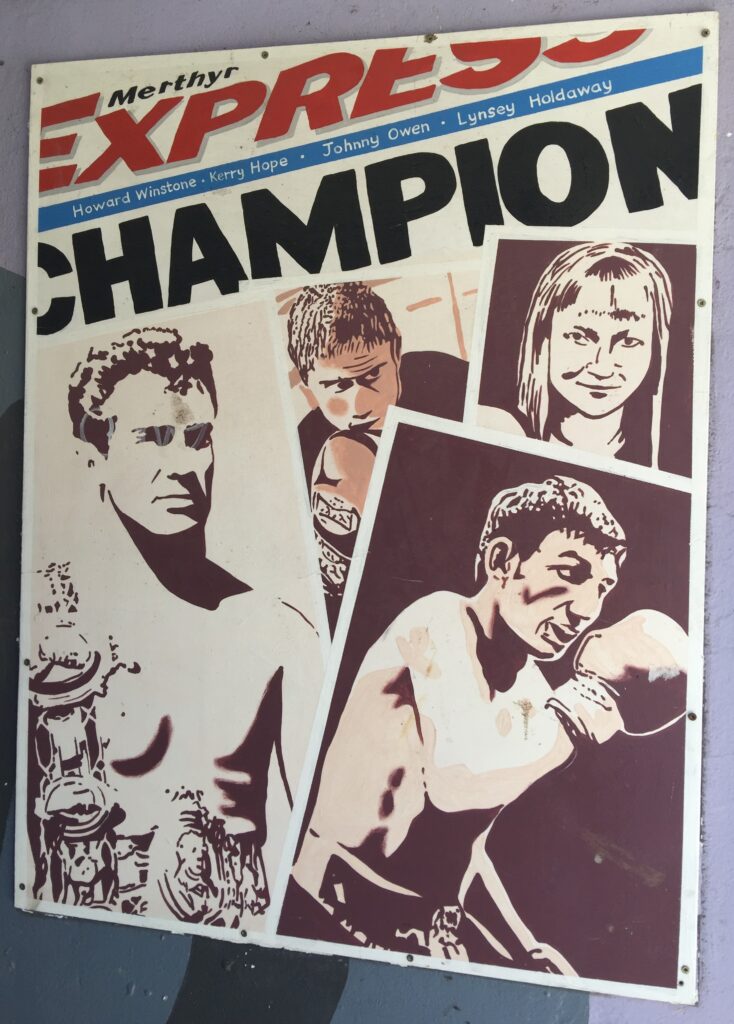

But to focus solely on Wilde in Merthyr boxing terms is to scratch only the surface. Dotted around the town you will find statues and tributes to the likes of Wilde, Howard Winstone, Eddie Thomas and the tragic ‘Merthyr Matchstick’ Johnny Owen. Merthyr and boxing go hand in glove.

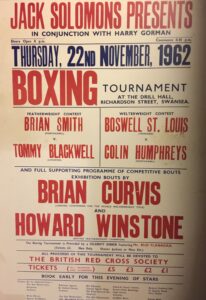

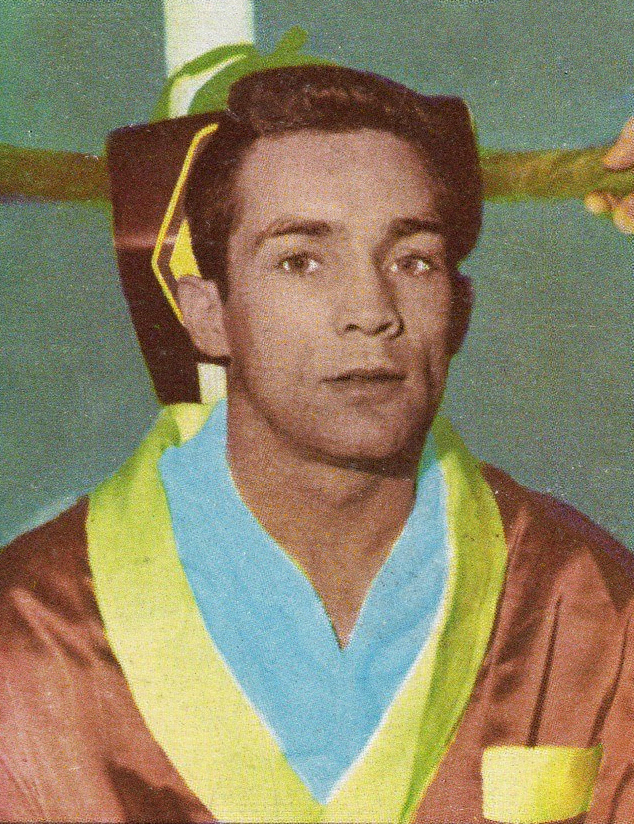

Winstone, born April 15, 1939, – was another Welsh world champion boxer from Merthyr.

As an amateur, he won the Amateur Boxing Association bantamweight title in 1958, and a Commonwealth Games gold medal at the 1958 British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Cardiff.

In September 1965, ‘The Welsh Wizard’ challenged for the WBA and WBC world featherweight titles held by the Mexican southpaw, Vicente Saldivar. The fight was held at Earls Court Arena, London, and Saldivar won on points over 15 rounds.

In March 1966, Winstone defended his European title against Andrea Silanos in Italy, winning by a technical knockout in the 15th round. In September the same year, he defended it against Belgian Jean de Keers at Wembley and won on a TKO in three rounds.

Three months later, he defended his British and European titles against the Welsh featherweight Lennie Williams, defeating him at Port Talbot in eight rounds.

By June 1967 he was ready for another world title challenge against Saldivar, this time in Cardiff, but again lost on points, although the decision favoured Saldivar by only half a point.

Four months later, he fought Saldivar yet again, this time in Mexico City, but lost after being knocked down in the seventh and 12th rounds.

After his latest successful defence, Saldivar announced his retirement leaving his world title vacant. In January 1968, Winstone fought the Japanese Mitsunori Seki for the vacant WBC world featherweight title at the Royal Albert Hall.

He won when the fight was stopped in the ninth due to a cut eye, and so finally gained that elusive world title. Saldivar was in the audience to see his vacated title won by his old rival.

In July 1968 he defended his newly won world title against the Cuban, Jose Legra, at Porthcawl, Wales. Although Winstone had beaten Legra twice before, he was knocked down twice in the first round. He continued fighting, but he sustained a badly swollen left eye, which caused the bout to be stopped in the fifth round. Having lost the world title in his first defence, Winstone decided to retire at the age of 29.

He continued living in Merthyr Tydfil after retirement and, in 1968, he was awarded the MBE for services to boxing. Later, he was made a Freeman of Merthyr Tydfil due to his boxing accomplishments.

He died from kidney disease on 30 September 2000, aged 61, and a year after his death, a bronze statue of Winstone by Welsh sculptor David Petersen was unveiled in St Tydfil’s Square.

In 2005, he beat Owen Money, Richard Trevithick, Joseph Parry and Lady Charlotte Guest to be named ‘Greatest Citizen of Merthyr Tydfil’, in a public vote competition run by Cyfarthfa Castle and Museum as part of the centenary celebrations to mark Merthyr Tydfil’s incorporation as a county borough in 1905.

The life of Howard Winstone was made into a feature film called Risen, starring British actor Stuart Brennan as Winstone, which was released in 2011.

Winstone was to come under the wing of Thomas, who earned the nickname ‘The Merthyr Marvel’ during his career as both a Welsh boxing champion and successful boxing manager.

Thomas was born in Heolgerrig, Merthyr Tydfil, on July 27, 1926. After a highly successful amateur career, he turned professional in 1946, winning the Welsh welterweight title in 1948, the British title in 1949 and the European crown in 1951.

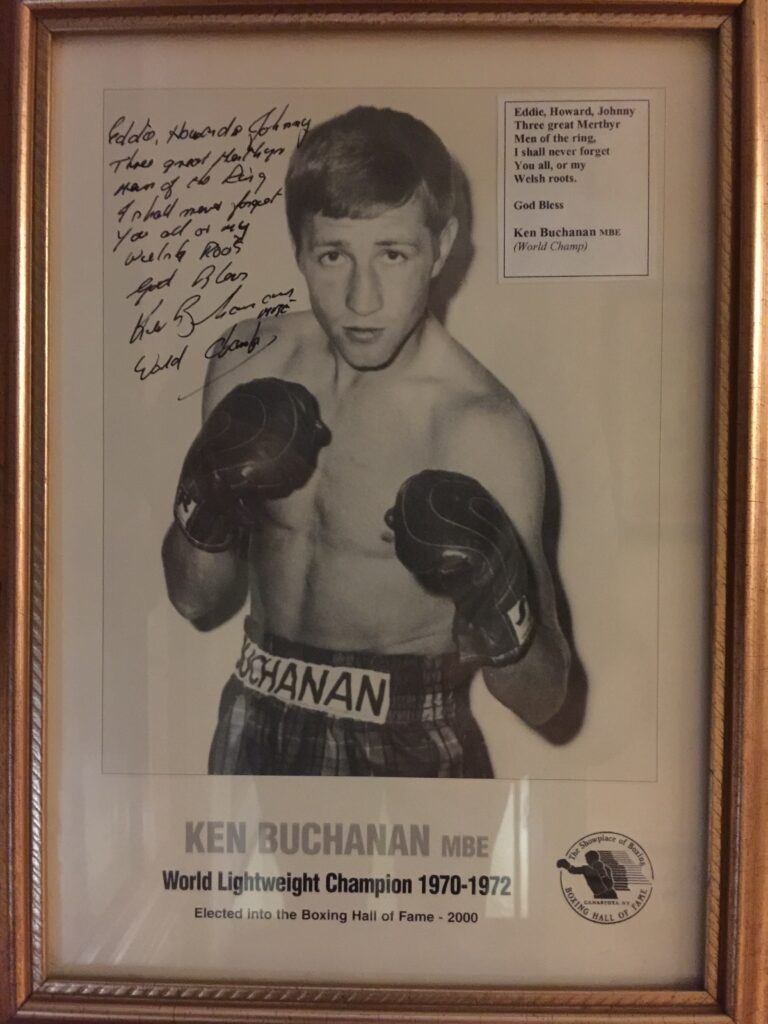

Retiring in 1954, he became the manager of two of Britain’s most successful boxing champions, Winstone and Ken Buchanan.

Thomas had a successful business career and spent time as Mayor of Merthyr Tydfil. A BBC TV programme, Champ from Colliers Row, was made about him in 1997, shortly after his death.

Johnny Owen, born John Richard Owens on January 7, 1956, never achieved his ambition of becoming world bantamweight champion.

His fragile appearance earned him many epithets, including ‘the Bionic Bantam’ and ‘the Merthyr Matchstick’. During his brief career, he held the bantamweight championships of Great Britain and Europe and became the first ever Welsh holder of the bantamweight championship of the Commonwealth.

But tragedy struck when he challenged champion Lupe Pintor for his version of the world bantamweight title on September 19, 1980, after losing a torturously difficult contest by way of 12th-round knockout.

Owen never regained consciousness, fell into a coma and died in Los Angeles seven weeks later.

In an academic publication by Martin Johnes entitled Stories of a Post-industrial Hero: The Death of Johnny Owen, it was noted that Owen was certainly not forgotten after his death.

“In 1981 a pub opened in Merthyr named ‘The Matchstick Man’. Four years later a memorial statue was unveiled at Merthyr’s hospital which had benefitted from an appeal fund set up after Owen’s death.

“In the 1990s a film script was written, although it was never made, and his belts were put on display in a Merthyr musuem.

“Biographies of him were published in 2005 and 2006 and both brought renewed media attention. In July 2006 a play about Owen was performed at the Wales Millennium Centre. That year the South Wales Echo called him “one of south Wales’s finest sons”.

“The spark for some of this new interest came in 2002 when the BBC broadcast a poignant television documentary about Owen’s father’s trip to Mexico to meet Pintor and Pintor’s subsequent return visit to unveil a statue of Owen in Merthyr town centre.

“Paid for by a public appeal, it was Merthyr’s third statue of a boxer and it added to the depictions of Eddie Thomas and Howard Winstone that had been unveiled in 2000 and 2001.

“Owen had joined the legend of how something about the valleys’ history produced not just boxers, but world-class boxers. This legend was nothing new. In 1961, Eddie Thomas had claimed that boxers in his small Dowlais amateur gym had the sport in their blood due to mixed marriages between strong Welsh and Irish people. The ‘instinct to box and fight’ was, he felt, passed down through the generations.

“This might sound nonsensical but people saw evidence that something special was going on. A 1973 short story claimed: ‘No less than three champions of the world had been born within a radius of six miles of where they sat. In a pub down the road, there were signed photographs of all three; Tom Thomas, Freddy Welsh, Jimmy Wilde. And hadn’t they all fought their way over the tips and out of the pit in the first instance? It was a local tradition with which they had all grown up. Weren’t they, after all, rather special people?’

“Journalists and local history projects talked of boxing being embedded in Merthyr’s psyche and made connections between the popularity of boxing in Merthyr and the town’s hard industrial past. Owen added to that tale.

“His biographies drew on the idea that somehow boxing was innate to Merthyr. One claimed that Owen had the steel of Welsh industrial valleys coursing through his veins and that the fatal punch knocked out the dreams of his followers ever getting out of Merthyr’s ‘slow-death poverty’.

“It noted the history of struggle for better social and working conditions and political rights, concluding that Merthyr was ‘born out of fight’. Thus, the writer thought: ‘Fighting, in one guise or another, is in the blood of everyone born in Merthyr Tydfil. It has to be. It’s locked up in the genes, part of the evolutionary process of belonging to this great town. The Owens family go back a long way in Merthyr. They were a family of fighters and survivors. They still are. It’s in their blood’.”

BACK TO HOME PAGE