Tommy Cooper

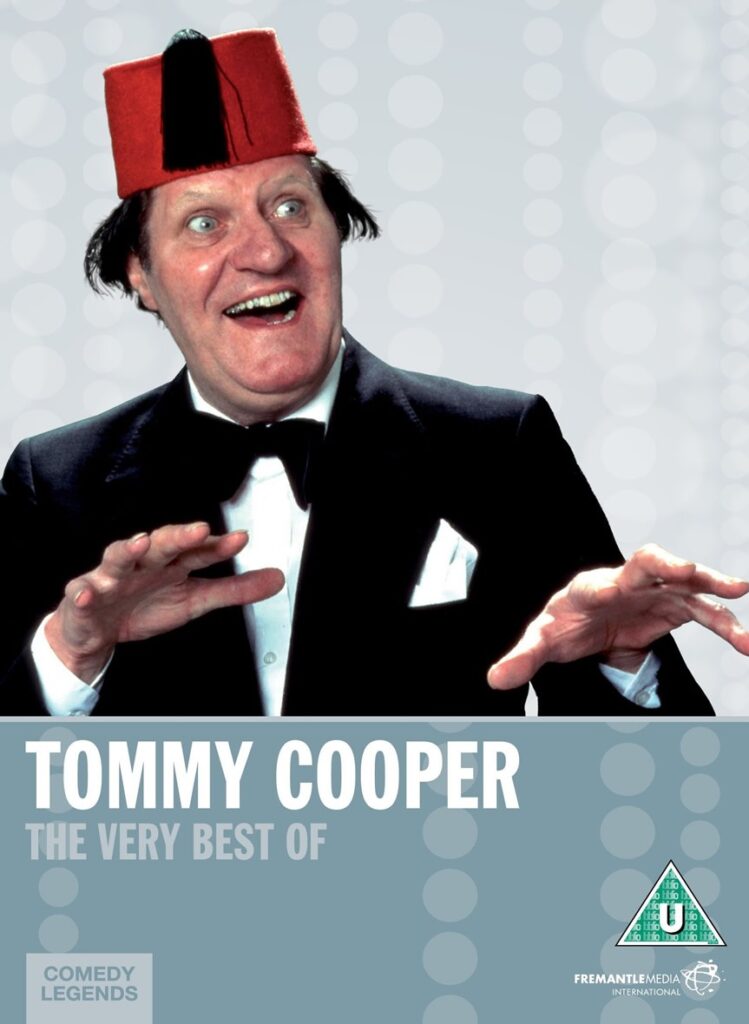

TOMMY COOPER was a one-of-a-kind comedian – the trademark fez, distinctive laugh, his clumsy, bewildered delivery and seemingly botched magic tricks all combined to make him a true comedy icon.

He didn’t have to say anything to make his audience laugh, his somewhat puzzled facial expression and shambling appearance alone were enough.

Fellow magician Paul Daniels was in awe of the great man: “He did a great after-dinner speech at the [Grand Order of] Water Rats. This great big man just stood up. That’s all he did. He just stood up and the place was in absolute hysterics at a man standing up.

“Now, I don’t care how much you study comedy, you can’t define that, that ability to fill a room with laughter because you are emanating humour. After several minutes of laughter he turned to his wife and said, “I haven’t said anything yet.” And the whole place went up again.”

Clearly not getting the joke, the BBC, in an audition for new talent, once described him as an “unattractive young man with an extremely unfortunate appearance”.

Tommy Cooper had that indefinable something. A giant talent housed within a body every bit as big as its ability. Although the hallmark of his act was to get magic tricks wrong, he was in reality an accomplished magician and member of the Magic Circle. To keep the audience on their toes Cooper would throw in an occasional trick that worked when it was least expected.

For decades, Cooper was a top-liner in variety with his turn as the conjurer whose tricks never succeeded, but it was his television work that raised him to national prominence. However, Cooper was influenced by comics from the big screen, stage and radio, such as Laurel and Hardy, Will Hay, Max Miller, Bob Hope and Robert Orben.

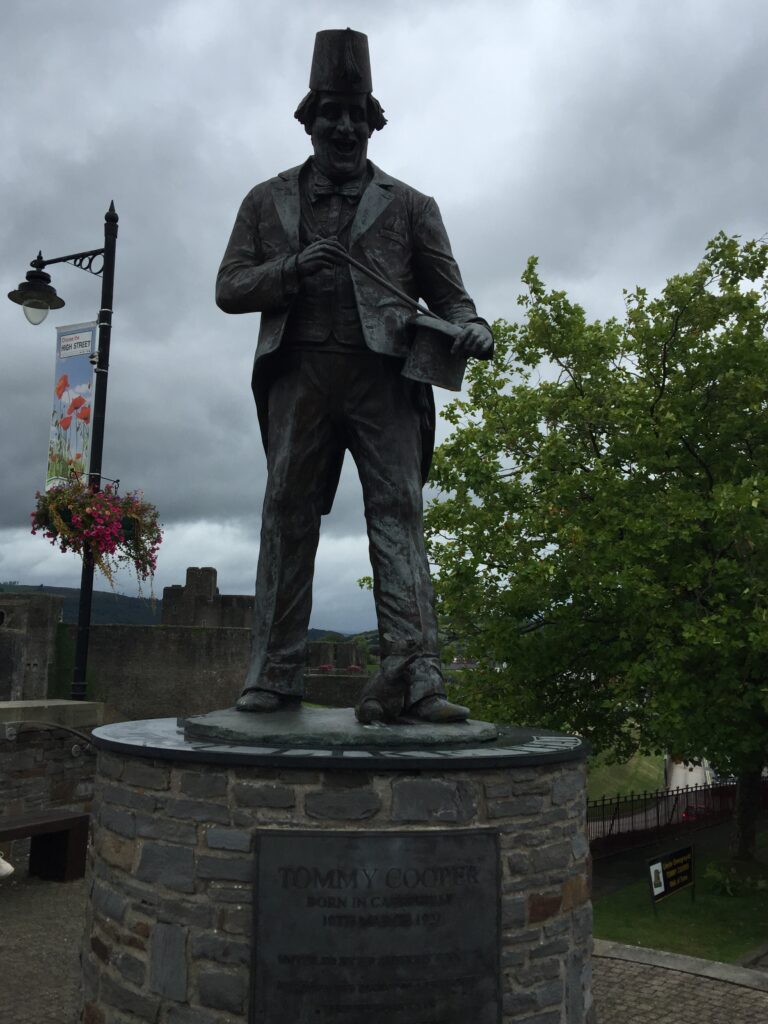

Cooper was born in Caerphilly, south Wales, on March 19, 1921. He was two months premature and the doctor who delivered him didn’t hold out much hope for his survival. However, his grandmother kept him alive on drops of brandy and condensed milk and little Tom got stronger as each day passed.

When he was eight years-old his aunt Lucy bought him a magic set and Cooper spent hours playing with it and perfecting the tricks. At the age of 16 he got a job on board a boat as an apprentice shipwright and it was here that he gave his first public performance.

Each trick he performed went disastrously wrong. He was supposed to pull a series of coloured handkerchiefs from a cylinder, but they got stuck, a card fell out of his sleeve, Cooper ran out of the room, tears running down his face. When he finally managed to calm down he began to analyse just why he’d messed it up. “I got stage fright.” He would recall years later. “That’s why it all went wrong. But then I thought to myself, well, it might have all gone wrong but I got a laugh. Perhaps I should concentrate on that.”

In 1940, Cooper got his call-up papers and went into the Royal Horse Guards. Six foot four with size 13 boots, he must have looked an impressive sight. “On the first day there I put my foot in the stirrup but the saddle slipped and I ended up underneath the horse’s belly. Everyone was sitting on their horse except me.”

He joined Montgomery’s Desert Rats in Egypt. It was while entertaining the troops in the concert party that he began perfecting his act of the magician whose tricks go wrong.

One evening in Cairo, during a sketch in which he was supposed to be in a costume that required a pith helmet, having forgotten the prop Cooper reached out and borrowed a fez from a passing waiter, which got huge laughs. He wore a fez when performing after that, the prop becoming an instantly recognisable trademark and later being described as “an icon of 20th Century comedy”.

In March 1977, at a Variety Club lunch in honour of Tommy’s 30 years in showbiz, he stood up in front of 400 guests. On cue, each one of them reached into their pocket and pulled out a fez which they stuck on top of their heads. Tom looked at them all for a moment, then, without saying a word, reached into his own pocket, pulled out a fisherman’s cap and put it on. The whole place fell about.

In 1947, a few months after leaving the army, Cooper went professional. He made his TV debut as early as December of that year in The Leslie Henson Christmas Eve Party.

He later toured the variety theatre circuit, but only got to play minor venues and had to supplement his wages by working as a barrow boy in west London’s Portobello Road market.

Finally, after doing the circuit and working hard for two years he got a break at London’s famous Windmill Theatre. He quickly gained a reputation as a genuine funnyman and class act.

Suddenly, it seemed that everyone wanted him. Between 1951 and 1952 he appeared at the London Hippodrome in Encore Des Follies and also got his big break in television when he starred in the BBC series It’s Magic. He made his debut at the London Palladium and did a tour for the all-important Moss Empire circuit, where he was booked as one of the bill-toppers.

By 1957 was a well-known star. He had a successful debut at the Hotel Flamingo in Las Vegas and had to turn down a season at the Radio City Music Hall because he was already booked solid for the next two years in England. His first TV series, Life With Cooper, was so successful that even before the end of its run he was being offered another series.

In 1963, he returned to America to record two Ed Sullivan shows. Sullivan, who at the time had one of the most influential shows on US TV, introduced Cooper for the second show as “The funniest man to ever appear on this stage.”

Throughout the ’60s and ’70s, he cemented his place in the public’s affections. In 1969, he was voted ITV’s Personality of the Year.

By the mid-1970s alcohol had started to erode Cooper’s professionalism and club owners complained that he turned up late or rushed through his show. In addition, he suffered from chronic indigestion, lumbago, sciatica, bronchitis and severe circulation problems in his legs.

When Cooper realised the extent of his maladies he cut down on his drinking, and the energy and confidence returned to his act. However, he never stopped drinking and could be fallible; on an otherwise triumphant appearance with Michael Parkinson he is said to have fogotten to set the safety catch on the guillotine illusion into which he had cajoled Parkinson, and only a last-minute intervention by the floor manager saved the talk show host from serious injury or worse.

Cooper was a heavy smoker as well as an excessive drinker. He experienced a decline in health during the late 1970s, suffering a heart attack in 1977 while performing a show in Rome. Three months later he was back on television in Night Out at the London Casino.

Stories about Tommy Cooper have become legend. A funnyman on screen, he was also a great practical joker off it.

John Fisher writes in his biography of Cooper: “Everyone agrees that he was mean. Quite simply, he was acknowledged as the tightest man in show business, with a pathological dread of reaching into his pocket.”

One of Cooper’s stunts was to pay the exact taxi fare and when leaving the cab slip something into the taxi driver’s pocket, saying, “Have a drink on me.” That something would turn out to be a tea bag.

His punctuality, or lack of it, was famous amongst his fellow performers. Directors would call rehearsals at 11am and hope Cooper would arrive by two.

One of his great friends, Eric Sykes, recalled the time that the two were making a film together and had decided to meet in a pub near the studios at noon.

“So noon comes and goes and there’s no sign of Tommy. The pub is beginning to fill up and I, being a stickler for punctuality, am getting very annoyed. It’s now 12.15 and I’m telling the producer that when Tom does arrive he’s going to get a very big piece of my mind.

“At 12.45 – the pub is totally full by now – the front door swings open and standing there is Tommy wearing a bowler hat and a pair of pyjamas. He walks up to our table and says, “I’m sorry I’m late. I couldn’t get up.”

His humour knew no class barriers either. Even The Queen of England wasn’t safe from Tommy’s wit. Cooper was introduced to Her Majesty after a Royal Command Performance.

“Do you think I was funny?” he asked her.

“Yes, Tommy.” replied The Queen.

“You really thought I was funny?”

“Yes, of course I thought you were funny.”

“Did your mother think I was funny?”

“Yes, Tommy. We both thought you were funny.”

“Do you mind if I ask you a personal question?”

“No, but I might not be able to give you a full answer.”

“Do you like football?”

“Well, not really.”

“Can I have your Cup Final tickets?”

If his on-stage persona came about by accident, Cooper was meticulous in honing it for every last laugh. A notoriously demanding perfectionist, he was also a hard worker, reputedly performing up to 52 shows a week while at The Windmill.

His appetite for work was so voracious that few were surprised that his death came on stage, doing what he loved. And such was his reputation as a relentless joker that when he collapsed during a live televised show at Her Majesty’s Theatre on April 15, 1984, most of the audience thought it was just another of his gags.

And so the laughs were still ringing out as Cooper, slumpped on the stage, had the curtain brought down on him for the final time and the show cut to a commercial break.

The show’s host, one of Cooper’s great friends, Jimmy Tarbuck, recalled the moment: “As usual, he was supposed to make a mess of the last trick. He was wearing a long cloak from which he was supposed to start bringing out large objects. Then a ladder would come through his legs followed by a milk churn and a long pole.

“When Tommy fell backwards I thought he’d put another gag in. I thought he was going to do some levitation trick from under his cloak. We all expected him to get up and we waited for the roar of laughter. It was terrible when he didn’t.” Ten minutes later Tommy Cooper died on the way to hospital.

That rarest of things, a performer equally as loved and respected by his peers as by his fans, Cooper’s child-like vulnerability and deceptively simple brand of humour made him the most loved and impersonated of comedians. From a child in the school playground to actors of the stature of Sir Anthony Hopkins, Tommy was the ideal source of affectionate impersonation.

Tommy Cooper’s secret for success, like all truly great comedy, should never be exposed to close scrutiny. That it was real and that he possessed something which elevated his comedy to the heights of genuine art, should just be accepted and cherished.

The Tommy Cooper Society was set up in Caerphilly in 2002 and raised £45,000 for a statue of the comedian to be erected opposite the town’s castle. The statue of Cooper was unveiled in his birthplace in 2008 by Hopkins, who is patron of the Tommy Cooper Society. The statue was sculpted by James Done.

Hip-hop duo Dan le Sac Vs Scroobius Pip wrote the song Tommy C, about Cooper’s career and death, which appears on their 2008 album, Angles.

In August 2004, 20 years after his death, he was voted the funniest Briton of all time in a poll conducted by the Reader’s Digest magazine. In a 2005 poll, The Comedians’ Comedian, comedians and comedy insiders voted Cooper the sixth greatest comedy act ever.

Jerome Flynn has toured with his own tribute show to Cooper called Just Like That. In 2010 Cooper was portrayed by Clive Mantle in a stage show, Jus’ Like That! A Night Out with Tommy Cooper, at the Edinburgh Festival.

In 2012 the British Heart Foundation ran a series of advertisements featuring Tommy Cooper to raise awareness of heart conditions. These included posters bearing his image, together with radio commercials featuring classic Cooper jokes.

Being Tommy Cooper, a play written by Tom Green and starring Damian Williams, was produced by Franklin Productions and toured the UK in 2013.

In 2014, with the support of The Tommy Cooper Estate and Cooper’s daughter Victoria, a new tribute show, Just Like That! The Tommy Cooper Show, commemorating 30 years since the comedian’s death was produced by Hambledon Productions. The production moved to the Museum of Comedy in Bloomsbury, London, from September 2014 and continued touring throughout the UK.

In May 2016, a blue plaque in memory of Cooper was unveiled at his former home in Barrowgate Road, Chiswick. In August that year, it was announced that the Victoria and Albert Museum had acquired 116 boxes of Cooper’s papers and props, including his ‘gag file’, in which the museum said he had used a system to store his jokes alphabetically “with the meticulousness of an archivist”.

In 2017, a world record attempt for the most Tommy Cooper impressionists at one venue was held at Caerphilly Castle. The ‘Fez-tival’ – named after the entertainer’s famous hat – aimed to encourage a new generation of comedians and magicians.

RETURN TO WELSH GREATS IN PROFILE

BACK TO HOME PAGE