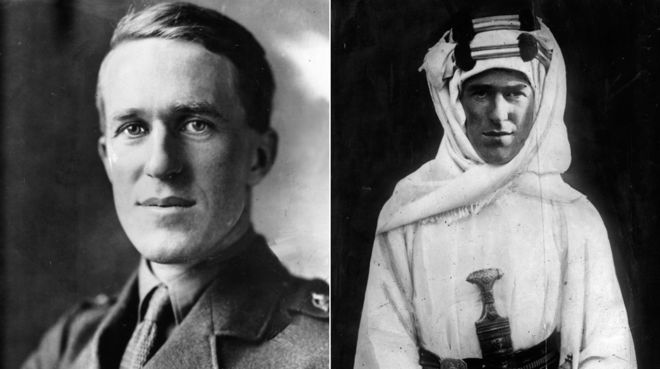

TE Lawrence

COLONEL THOMAS EDWARD LAWRENCE CB DSO was a Welsh-born archaeologist, army-officer, diplomat, and writer who became famous for his extraordinary work in the Middle East as a fighter and a negotiator during and following World War I.

Renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–1918) against the Ottoman Empire, he was a man who forged strong relationships between cultures through his compassion for, and his knowledge of, the people themselves.

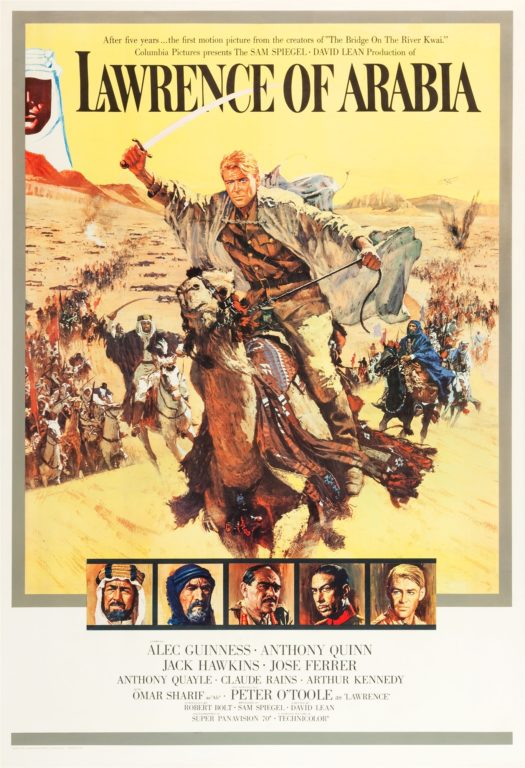

The breadth and variety of his activities and associations and his ability to describe them vividly in writing, earned him international fame as Lawrence of Arabia, a title used for the 1962 film starring Peter O’Toole, based on his wartime activities.

He was born out of wedlock in August 1888 to Sarah Junner, a governess, and Sir Thomas Chapman, 7th Baronet, an Anglo-Irish nobleman. Chapman left his wife and family in Ireland to cohabit with Junner. Chapman and Junner called themselves Mr and Mrs Lawrence, using the surname of Sarah’s likely father; her mother had been employed as a servant for a Lawrence family when she became pregnant with Sarah.

In 1896, the Lawrences moved to Oxford, where Thomas attended the High School and then achieved a Welsh scholarships to study history at Jesus College, Oxford, from 1907 to 1910. Between 1910 and 1914 he worked as an archaeologist for the British Museum, chiefly at Carchemish in Ottoman Syria.

Soon after the outbreak of war in 1914 he volunteered for the British Army and was stationed at the Arab Bureau intelligence unit in Egypt.

In 1916, he travelled to Mesopotamia and to Arabia on intelligence missions and quickly became involved with the Arab Revolt as a liaison to the Arab forces, along with other British officers, supporting the Arab Kingdom of Hejaz’s independence war against its former overlord, the Ottoman Empire. He worked closely with Emir Faisal, a leader of the revolt, and he participated, sometimes as leader, in military actions against the Ottoman armed forces, culminating in the capture of Damascus in October 1918.

After the First World War, Lawrence joined the British Foreign Office, working with the British government and with Faisal. In 1922, he retreated from public life and spent the years until 1935 serving as an enlisted man, mostly in the Royal Air Force, with a brief period in the Army.

During this time he published his best-known work, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, an autobiographical account of his participation in the Arab Revolt. He also translated books into English and wrote The Mint, which detailed his time in the Royal Air Force working as an ordinary aircraftman.

He corresponded extensively and was friendly with well-known artists, writers, and politicians.

For the RAF, he participated in the development of rescue motorboats.

Lawrence’s public image resulted in part from the sensationalised reporting of the Arab revolt by American journalist Lowell Thomas, as well as from Seven Pillars of Wisdom. In 1935, Lawrence was fatally injured in a motorcycle accident in Dorset.

Lawrence was born on August 16, 1888, in Tremadog, Carnarvonshire, north Wales, in a house named ‘Gorphwysfa’, later known as Snowdon Lodge. From Wales, the family moved to Kirkcudbright, Galloway, in southwestern Scotland, then to Dinard in Brittany, then to Jersey.

In 1914, his father inherited the Chapman baronetcy based at Killua Castle, the ancestral family home in County Westmeath, Ireland.

Lawrence attended the City of Oxford High School for Boys from 1896 until 1907, where one of the four houses was later named ‘Lawrence’ in his honour; the school closed in 1966. Lawrence and one of his brothers became commissioned officers in the Church Lads’ Brigade at St Aldate’s Church.

Lawrence claimed that he ran away from home around 1905 and served for a few weeks as a boy soldier with the Royal Garrison Artillery at St Mawes Castle in Cornwall.

From 1907 to 1910, Lawrence read history at Jesus College, Oxford. In July and August 1908 he cycled 2,200 miles solo through France to the Mediterranean and back researching French castles. In the summer of 1909, he set out alone on a three-month walking tour of crusader castles in Ottoman Syria, during which he travelled 1,000 miles on foot.

While at Jesus, he was a keen member of the University Officers’ Training Corps (OTC). He graduated with First Class Honours after submitting a thesis titled ‘The Influence of the Crusades on European Military Architecture — to the End of the 12th Century’.

Although his family did not stay in Wales long after he was born, he wrote letters describing his explorations of Welsh castles, including one to his mother penned in Caerphilly in 1907.

In his letter, he first describes Kidwelly Castle, which he had visited a couple of days earlier, as “just ruined enough to be interesting”. He described its ovens and dungeons as “specially remarkable features”.

He goes on to describe Caerphilly Castle as simply “magnificent” with features which could not be paralleled.

In 1910, Lawrence was offered the opportunity to become a practising archaeologist at Carchemish, in the expedition that DG Hogarth was setting up on behalf of the British Museum. He sailed for Beirut in December 1910 and went to Byblos, where he studied Arabic.

He then went to work on the excavations at Carchemish, near Jerablus in northern Syria, where he worked under Hogarth, R Campbell Thompson of the British Museum and Leonard Woolley until 1914.

At Carchemish, Lawrence was frequently involved in a high-tension relationship with a German-led team working nearby on the Baghdad Railway at Jerablus. While there was never open combat, there was regular conflict over access to land and treatment of the local workforce; Lawrence gained experience in Middle Eastern leadership practices and conflict resolution.

In January 1914, Woolley and Lawrence were co-opted by the British military as an archaeological smokescreen for a British military survey of the Negev Desert. They were funded by the Palestine Exploration Fund to search for an area referred to in the Bible as the Wilderness of Zin, and they made an archaeological survey of the Negev Desert along the way. The Negev was strategically important, as an Ottoman army attacking Egypt would have to cross it.

Woolley and Lawrence subsequently published a report of the expedition’s archaeological findings, but a more important result was updated mapping of the area, with special attention to features of military relevance such as water sources.

Following the outbreak of hostilities in August 1914, Lawrence was summoned by renowned archaeologist and historian Lt Cmdr David Hogarth, his mentor at Carchemish, to the new Arab Bureau intelligence unit in Cairo, and he arrived in Cairo on December 15, 1914.

The situation was complex during 1915. There was a growing Arab-nationalist movement within the Arabic-speaking Ottoman territories, including many Arabs serving in the Ottoman armed forces. They were in contact with Sharif Hussein, Emir of Mecca, who was negotiating with the British and offering to lead an Arab uprising against the Ottomans. In exchange, he wanted a British guarantee of an independent Arab state including the Hejaz, Syria, and Mesopotamia.

Such an uprising would have been very helpful to Britain in its war against the Ottomans, greatly lessening the threat against the Suez Canal. However, there was resistance from French diplomats who insisted that Syria’s future was as a French colony, not an independent Arab state.

At the Arab Bureau, Lawrence supervised the preparation of maps, produced a daily bulletin for the British generals operating in the theatre and interviewed prisoners. He was an advocate of a British landing at Alexandretta which never came to pass. He was also a consistent advocate of an independent Arab Syria.

The situation came to a crisis in October 1915, as Sharif Hussein demanded an immediate commitment from Britain, with the threat that he would otherwise throw his weight behind the Ottomans. This would create a credible Pan-Islamic message that could have been very dangerous for Britain, which was in severe difficulties in the Gallipoli Campaign. The British replied with a letter from High Commissioner McMahon that was generally agreeable while reserving commitments concerning the Mediterranean coastline and Holy Land.

In the spring of 1916, Lawrence was dispatched to Mesopotamia to assist in relieving the Siege of Kut by some combination of starting an Arab uprising and bribing Ottoman officials. This mission produced no useful result.

Meanwhile, the Sykes–Picot Agreement was being negotiated in London without the knowledge of British officials in Cairo, which awarded a large proportion of Syria to France. Further, it implied that the Arabs would have to conquer Syria’s four great cities if they were to have any sort of state there: Damascus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo. It is unclear at what point Lawrence became aware of the treaty’s contents.

The Arab Revolt began in June 1916, but it bogged down after a few successes, with a real risk that the Ottoman forces would advance along the coast of the Red Sea and recapture Mecca. On October 16, 1916, Lawrence was sent to the Hejaz on an intelligence-gathering mission. He interviewed Sharif Hussein’s sons Ali, Abdullah, and Faisal, and he concluded that Faisal was the best candidate to lead the Revolt.

In November, SF Newcombe was assigned to lead a permanent British liaison to Faisal’s staff. Newcombe had not yet arrived in the area and the matter was of some urgency, so Lawrence was sent in his place. In late December 1916, Faisal and Lawrence worked out a plan for repositioning the Arab forces to prevent the Ottoman forces around Medina from threatening Arab positions and putting the railway from Syria under threat.

Lawrence’s most important contributions to the Arab Revolt were in the area of strategy and liaison with British armed forces, but he also participated personally in several military engagements including, on January 23, 1918, the battle of Tafileh, a region southeast of the Dead Sea; the battle was a defensive engagement that turned into an offensive rout and was described in the official history of the war as a “brilliant feat of arms”. Lawrence was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his leadership at Tafileh and was promoted to lieutenant colonel.

Lawrence made a 300-mile personal journey northward in June 1917, on the way to Aqaba, visiting Ras Baalbek, the outskirts of Damascus, and Azraq, Jordan. He met Arab nationalists, counselling them to avoid revolt until the arrival of Faisal’s forces, and he attacked a bridge to create the impression of guerrilla activity. His findings were regarded by the British as extremely valuable and there was serious consideration of awarding him a Victoria Cross; in the end, he was invested as a Companion of the Order of the Bath and promoted to Major.

Lawrence travelled regularly between British headquarters and Faisal, co-ordinating military action. But by early 1918, Faisal’s chief British liaison was Colonel Pierce Charles Joyce, and Lawrence’s time was chiefly devoted to raiding and intelligence-gathering.

The chief elements of the Arab strategy which Faisal and Lawrence developed were to avoid capturing Medina, and to extend northwards through Maan and Dera’a to Damascus and beyond. Faisal wanted to lead regular attacks against the Ottomans, but Lawrence persuaded him to drop that tactic.

Lawrence wrote about the Bedouin as a fighting force: “The value of the tribes is defensive only and their real sphere is guerilla warfare. They are intelligent, and very lively, almost reckless, but too individualistic to endure commands, or fight in line, or to help each other. It would, I think, be possible to make an organized force out of them.… The Hejaz war is one of dervishes against regular forces — and we are on the side of the dervishes. Our text-books do not apply to its conditions at all.”

Medina was an attractive target for the revolt as Islam’s second holiest site, and because its Ottoman garrison was weakened by disease and isolation. It became clear that it was advantageous to leave it there rather than try to capture it, while continually attacking the Hejaz railway south from Damascus without permanently destroying it. This prevented the Ottomans from making effective use of their troops at Medina, and forced them to dedicate many resources to defending and repairing the railway line.

In 1917, Lawrence proposed a joint action with the Arab irregulars and forces including Auda Abu Tayi, who had previously been in the employ of the Ottomans, against the strategically located but lightly defended town of Aqaba on the Red Sea.

Lawrence carefully avoided informing his British superiors about the details of the planned inland attack, due to concern that it would be blocked as contrary to French interests. The expedition departed from Wejh on May 9, and Aqaba fell to the Arab forces on July 6, after a surprise overland attack which took the Turkish defences from behind.

After Aqaba, General Sir Edmund Allenby, the new commander-in-chief of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, agreed to Lawrence’s strategy for the revolt. Lawrence now held a powerful position as an adviser to Faisal and a person who had Allenby’s confidence, as Allenby acknowledged after the war: “I gave him a free hand. His cooperation was marked by the utmost loyalty, and I never had anything but praise for his work, which, indeed, was invaluable throughout the campaign. He was the mainspring of the Arab movement and knew their language, their manners and their mentality.”

Lawrence describes an episode on November 20, 1917, while reconnoitring Dera’a in disguise, when he was captured by the Ottoman military, heavily beaten, and sexually abused by the local bey and his guardsmen. Some scholars have stated that he exaggerated the severity of the injuries that he suffered, or alleged that the episode never actually happened. There is no independent testimony, but the multiple consistent reports and the absence of evidence for outright invention in Lawrence’s works make the account believable to his biographers.

Malcolm Brown, John E Mack, and Jeremy Wilson have argued that this episode had strong psychological effects on Lawrence, which may explain some of his unconventional behaviour in later life. Lawrence ended his account of the episode in Seven Pillars of Wisdom with the statement: “In Dera’a that night the citadel of my integrity had been irrevocably lost.”

Lawrence was involved in the build-up to the capture of Damascus in the final weeks of the war, but he was not present at the city’s formal surrender, much to his disappointment. He arrived several hours after the city had fallen, entering Damascus around 9am on October 1, 1918.

Lawrence was instrumental in establishing a provisional Arab government under Faisal in newly-liberated Damascus, which he had envisioned as the capital of an Arab state. Faisal’s rule as king, however, came to an abrupt end in 1920, after the battle of Maysaloun when the French Forces of General Gouraud entered Damascus under the command of General Mariano Goybet, destroying Lawrence’s dream of an independent Arabia.

During the closing years of the war, Lawrence sought to convince his superiors in the British government that Arab independence was in their interests, but he met with mixed success. The secret Sykes-Picot Agreement between France and Britain contradicted the promises of independence that he had made to the Arabs and frustrated his work.

Lawrence returned to the United Kingdom a full colonel. Immediately after the war, he worked for the Foreign Office, attending the Paris Peace Conference between January and May as a member of Faisal’s delegation. On May 17, 1919, a Handley Page Type O/400 taking Lawrence to Egypt crashed at the airport of Roma-Centocelle. The pilot and co-pilot were killed; Lawrence survived with a broken shoulder blade and two broken ribs.

In 1918, Lowell Thomas went to Jerusalem where he met Lawrence, “whose enigmatic figure in Arab uniform fired his imagination”, in the words of author Rex Hall. Thomas and his cameraman Harry Chase shot a great deal of film and many photographs involving Lawrence. Thomas produced a stage presentation entitled With Allenby in Palestine which included a lecture, dancing, and music and engaged in ‘Orientalism’, depicting the Middle East as exotic, mysterious, sensuous, and violent.

The show premiered in New York in March 1919. He was invited to take his show to England, and he agreed to do so provided that he was personally invited by the King and provided the use of either Drury Lane or Covent Garden. He opened at Covent Garden on August 14, 1919, and continued for hundreds of lectures, “attended by the highest in the land”.

Initially, Lawrence played only a supporting role in the show, as the main focus was on Allenby’s campaigns; but then Thomas realised that it was the photos of Lawrence dressed as a Bedouin which had captured the public’s imagination, so he had Lawrence photographed again in London in Arab dress.

With the new photos, Thomas re-launched his show under the new title With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia in early 1920, which proved to be extremely popular. The new title elevated Lawrence from a supporting role to a co-star of the Near Eastern campaign and reflected a changed emphasis. Thomas’s shows made the previously obscure Lawrence into a household name.

Lawrence worked with Thomas on the creation of the presentation, answering many questions and posing for photographs. After its success, however, he expressed regret about having been featured in it.

Lawrence served as an advisor to Winston Churchill at the Colonial Office for just over a year, starting in February 1920. He hated bureaucratic work, writing on May 21, 1921, to Robert Graves: “I wish I hadn’t gone out there: the Arabs are like a page I have turned over; and sequels are rotten things. I’m locked up here: office every day and much of it”. He travelled to the Middle East on multiple occasions during this period, at one time holding the title of “chief political officer for Trans-Jordania”.

He campaigned actively for his and Churchill’s vision of the Middle East, publishing pieces in multiple newspapers, including The Times, The Observer, The Daily Mail and The Daily Express.

Lawrence had a sinister reputation in France during his lifetime and as an implacable ‘enemy of France’, the man who was constantly stirring up the Syrians to rebel against French rule throughout the 1920s. However, French historian Maurice Larès wrote that the real reason for France’s problems in Syria was that the Syrians did not want to be ruled by France, and the French needed a “scapegoat” to blame for their difficulties in ruling the country. Larès wrote that Lawrence is usually pictured in France as a Francophobe, but he was really a Francophile.

In August 1922, Lawrence enlisted in the Royal Air Force as an aircraftman, under the name John Hume Ross. At the RAF recruiting centre in Covent Garden, London, he was interviewed by recruiting officer Flying Officer WE Johns, later known as the author of the Biggles series of novels. Johns rejected Lawrence’s application, as he suspected that ‘Ross’ was a false name. Lawrence admitted that this was so and that he had provided false documents. He left, but returned some time later with an RAF messenger who carried a written order that Johns must accept Lawrence.

However, Lawrence was forced out of the RAF in February 1923 after his identity was exposed. He changed his name to TE Shaw and joined the Royal Tank Corps later that year. He was unhappy there and repeatedly petitioned to rejoin the RAF, which finally readmitted him in August 1925. A fresh burst of publicity after the publication of Revolt in the Desert resulted in his assignment to bases at Karachi and Miramshah in British India (now Pakistan) in late 1926, where he remained until the end of 1928. At that time, he was forced to return to Britain after rumours began to circulate that he was involved in espionage activities.

Lawrence continued serving in the RAF based at RAF Mount Batten, near Plymouth, RAF Calshot, near Southampton, and RAF Bridlington, East Riding of Yorkshire. He specialised in high-speed boats and professed happiness, and he left the service with considerable regret at the end of his enlistment in March 1935.

Lawrence was a keen motorcyclist and owned eight Brough Superior motorcycles at different times.

On May 13, 1935, Lawrence was fatally injured in an accident on his Brough Superior SS100 motorcycle in Dorset close to his cottage Clouds Hill, near Wareham, just two months after leaving military service. He died six days later on May 19, 1935, aged 46. The location of the crash is marked by a small memorial at the roadside.

One of the doctors attending him was neurosurgeon Hugh Cairns, who consequently began a long study of the loss of life by motorcycle dispatch riders through head injuries. His research led to the use of crash helmets by both military and civilian motorcyclists.

Lawrence, a competent speaker of French and Arabic, and reader of Latin and Ancient Greek, was a prolific writer throughout his life; he often sent several letters a day, and several collections of his letters have been published. He corresponded with many notable figures, including George Bernard Shaw, Edward Elgar, Churchill, Robert Graves, Noël Coward, EM Forster, Siegfried Sassoon, John Buchan, Augustus John and Henry Williamson.

Lawrence’s major published work is Seven Pillars of Wisdom, an account of his war experiences. In 1919, he was elected to a seven-year research fellowship at All Souls College, Oxford, providing him with support while he worked on the book. Certain parts of the book also serve as essays on military strategy, Arabian culture and geography, and other topics. He rewrote Seven Pillars of Wisdom three times, once after he lost the manuscript while changing trains at Reading railway station.

There are many alleged ’embellishments’ in Seven Pillars, though some allegations have been disproved with time, most definitively in Jeremy Wilson’s authorised biography. However, Lawrence’s own notebooks refute his claim to have crossed the Sinai Peninsula from Aqaba to the Suez Canal in just 49 hours without any sleep. In reality, this famous camel ride lasted for more than 70 hours and was interrupted by two long breaks for sleeping, which Lawrence omitted when he wrote his book.

Revolt in the Desert was an abridged version of Seven Pillars that he began in 1926 and that was published in March 1927.

A trust he set up from sales of his writing paid income either into an educational fund for children of RAF officers who lost their lives or were invalided as a result of service, or more substantially into the RAF Benevolent Fund.

Lawrence left The Mint unpublished, a memoir of his experiences as an enlisted man in the RAF. It was published posthumously, edited by his brother, Professor AW Lawrence.

Lawrence lived in a period of strong official opposition to homosexuality, but his writing on the subject was tolerant. He wrote to Charlotte Shaw, “I’ve seen lots of man-and-man loves: very lovely and fortunate some of them were.” He refers to “the openness and honesty of perfect love” on one occasion in Seven Pillars, when discussing relationships between young male fighters in the war.

There is considerable evidence that Lawrence was a masochist. He wrote in his description of the Dera’a beating that “a delicious warmth, probably sexual, was swelling through me,” and he also included a detailed description of the guards’ whip in a style typical of masochists’ writing. In later life, Lawrence arranged to pay a military colleague to administer beatings to him, and to be subjected to severe formal tests of fitness and stamina.

Angus Calder suggested in 1997 that Lawrence’s apparent masochism and self-loathing might have stemmed from a sense of guilt over losing his brothers Frank and Will on the Western Front, along with many other school friends, while he survived.

In 1955, Richard Aldington published Lawrence of Arabia: A Biographical Enquiry, a sustained attack on Lawrence’s character, writing, accomplishments, and truthfulness. Specifically, Aldington alleges that Lawrence lied and exaggerated continuously, promoted a misguided policy in the Middle East, that his strategy of containing but not capturing Medina was incorrect, and that Seven Pillars of Wisdom was a bad book with few redeeming features.

This has not prevented most post-Aldington biographers from expressing strong admiration for Lawrence’s military, political, and writing achievements.

Lawrence was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath on August 7, 1917, appointed a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order on May 10, 1918, awarded the Knight of the Legion of Honour (France) on May 30, 1916 and awarded the Croix de guerre (France) on April 16, 1918.

Peter O’Toole was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of Lawrence in the 1962 film Lawrence of Arabia. Lawrence was portrayed by Robert Pattinson in the 2014 biographical drama about Gertrude Bell, Queen of the Desert.

He was portrayed by Judson Scott in the 1982 TV series Voyagers! Ralph Fiennes portrayed Lawrence in the 1992 British made-for-TV movie A Dangerous Man: Lawrence After Arabia. Joseph A Bennett and Douglas Henshall portrayed him in the 1992 TV series The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles.

Lawrence was the subject of Terence Rattigan’s controversial play Ross, which explored Lawrence’s alleged homosexuality. Ross ran in London in 1960–61, starring Alec Guinness, who was an admirer of Lawrence, and Gerald Harper as his blackmailer, Dickinson.

Alan Bennett’s Forty Years On (1968) includes a satire on Lawrence. His 1922 retreat from public life forms the subject of Howard Brenton’s play Lawrence After Arabia, commissioned for a 2016 premiere at the Hampstead Theatre to mark the centenary of the outbreak of the Arab Revolt.

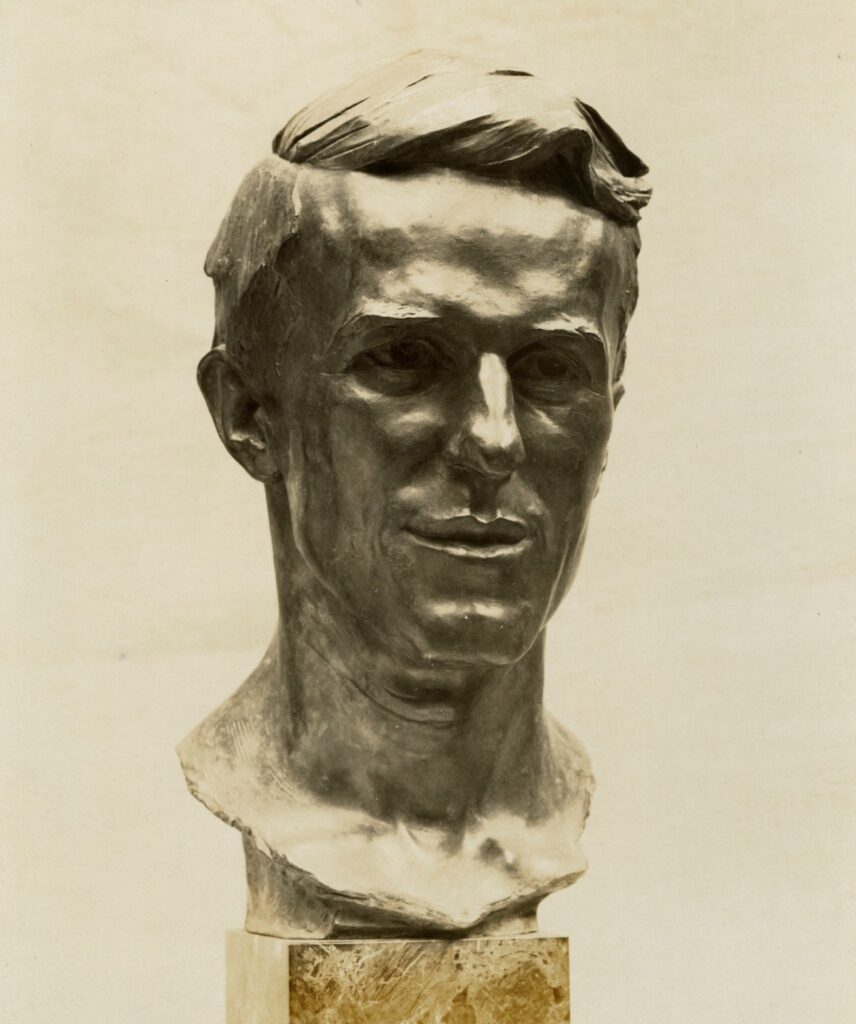

A bronze bust of Lawrence by Eric Kennington was placed in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral, London, on January 29, 1936, alongside the tombs of Britain’s greatest military leaders. A recumbent stone effigy by Kennington was installed in St Martin’s Church, Wareham, Dorset, in 1939.

An English Heritage blue plaque marks Lawrence’s childhood home at 2 Polstead Road, Oxford, and another appears on his London home at 14 Barton Street, Westminster. Lawrence appears on the album cover of Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band by The Beatles. In 2002, Lawrence was named 53rd in the BBC’s list of the 100 Greatest Britons following a UK-wide vote.

In 2018, Lawrence was featured on a £5 coin (issued in silver and gold) in a six-coin set commemorating the Centenary of the First World War, produced by the Royal Mint.

BACK TO HOME PAGE