Richard Burton

ONE of the greatest actors of his time, Richard Burton was the Welsh-speaking son of a coal miner from south Wales. Yet Burton would likely have swapped all his awards and accolades as a thespian to have donned the red shirt of Wales on the rugby field.

The acclaimed Welsh actor, some may say the greatest never to have won an Oscar, was fiercly proud of his country and, along with many thousands of his fellow countrymen, a slave to the oval ball.

Like many born in Wales, where the game is more a national religion than a sport, Burton played rugby union. He continued to play well into his early acting career, mainly at wing-forward. He only hung up his boots when contractual obligations to film and theatre producers forced him to do so.

Indeed, Burton once claimed he would much rather have played rugby for Wales than the career-defining role of Hamlet on stage.

During a break in filming on the 1971 film version of Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood in Fishguard, Burton once confided: “I can no longer bear to watch Wales play.”

Reminded that his beloved Wales were amid a ‘golden era’ of rugby greatness with such legendary figures as Barry John, Gareth Edwards and JPR Williams in the team, he growled: “You don’t have to tell me. That’s not the point.”

The point, he went on to explain to BBC reporter Denis Tuohy, was that if he planned to attend a match involving Wales, advance jitters would make acting work impossible for at least a fortnight beforehand.

Depending on the result, agony or ecstasy would then put him out of action for another few weeks. What had taken its toll, he said, was the sheer intensity of being Welsh, a heady combination of pride, passion and competitiveness.

So patriotic was Burton, in fact, that his movie contracts contained a clause that he did not have to work on the 1st of March, St David’s Day, the day honouring the patron saint of Wales.

His love of Wales extended to the language of his homeland also. “You haven’t heard the real beauty of The Bible until you have heard it in Welsh,” he once remarked.

And of his own acting career, he would say: “As the seventh son of a Welsh miner I knew hardship first hand. I come from the lower depths of the working class… one would expect me to be at my happiest playing peasants, people of the earth.

“But in actual fact I’m much happier playing princes and kings. Now whether this is a kind of sublimation of what I would like to be, or something like that, I don’t know, but certainly I’m never really very comfortable playing people from the working class.”

Conversely, he once noted: “The unfortunate thing is that everyone wants me to play a prince or a king… I’m always wearing a nightdress or a short skirt or something odd. I don’t want to do them, I don’t like them, I hate getting made up for them, I hate my hair being curled in the mornings, I hate tights, I hate boots, I hate everything. I’d like to be in a lounge suit, I’d like to be a sort of Welsh Rex Harrison and do nothing except lounge against a bar with a gin and tonic in my hand.”

Burton’s career could have branched in a different direction – that of 007. “I almost replaced Sean Connery as James Bond in Thunderball,” he once recalled.

“This was before Sean played Bond. My friend, the Irish producer Kevin McClory, wanted me. Kevin worked for Mike Todd on Around the World in 80 Days and I was impressed with his Irish rebelliousness. We Welsh have that, too, but not quite like the Irish, who transfuse it into their blood on the same day they are born.

“McClory promised [Alfred Hitchcock] would direct and I had great hopes for the project. It fell through, of course – and later Kevin made a bloody fortune, when Sean was Bond. I wonder sometimes how it might all have turned out. [Ian Fleming] was big on me for the role. Stewart Granger was next in line.”

Noted for his mellifluous baritone voice, Burton established himself as a formidable Shakespearean actor in the 1950s and he gave a memorable and long-running performance of Hamlet on Broadway in 1964.

Like his friends Olivier and O’Toole, Burton was a unique and utterly electrifying stage actor who commanded the rapt attention of his audience.

His Hamlet was the longest run of the play in Broadway history with 137 performances. It broke the record held by Gielgud, who played the part for 132 performances and who directed Burton’s Broadway production.

He is widely regarded as one of the most acclaimed actors of his generation, nominated for an Academy Award on no fewer than seven occasions – but never won an Oscar.

A recipient of BAFTAs, Golden Globes, and Tony Awards for Best Actor, Burton ascended into the ranks of the top box office stars during the 1960s and by the end of that decade was one of the highest-paid actors in the world, receiving fees of $1 million or more plus a share of gross receipts.

He earned his Oscar nominations for work like The Robe, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Becket and Equus. Burton was never out of the spotlight after marrying Hollywood icon Elizabeth Taylor in 1964 and the two maintained a volatile relationship for years to come that included remarriage and two divorces.

Burton’s purported failure to live up to expectations of critics and colleagues alike during a rollercoaster career added to his image as a great performer who had wasted his talent.

Richard Burton was born Richard Walter Jenkins on November 10, 1925, into a family of Welsh speakers in Pontrhydfen, south Wales. Jenkins, the 12th child of an impoverished coal miner, lost his mother when he was two years-old.

He was taken in and raised by his older sister, Cis, and her husband. “I shone in the reflection of her green-eyed, black-haired gypsy beauty,” Burton said of his sister/surrogate mother.

He was brought up in the same Port Talbot neighborhood where fellow Welsh acting star Anthony Hopkins later lived as a child. Incredibly, Burton, Ray Milland, Hopkins and Catherine Zeta-Jones were all born within a 10-mile radius in south-west Wales.

He would be taken under the wing of Philip Burton, a teacher who became the boy’s guardian and introduced him to the world of theatre. His stage debut came at Maesteg Town Hall.

Jenkins took the Burton surname and made his London acting debut as a Welsh youngster in the play The Druid’s Rest. Burton earned a scholarship to attend Oxford University and later joined the British air force during wartime.

After leaving the military in 1947, he continued his stage work and became known for his remarkable voice and oration, appearing in The Lady’s Not for Burning with Sir John Gielgud. Burton then made his film debut in 1949 with the production The Last Days of Dolwyn. The same year he wed actress Sybil Williams; the couple would eventually have two daughters.

Though met with varying degrees of commercial and critical regard over the course of his career, Burton went on to work in more than 40 films. He entered into a contract with Fox studios after Dolwyn and starred in My Cousin Rachel (1952), for which he earned his first Academy Award nomination for supporting actor.

The 1953 biblical story The Robe followed, for which he received an Oscar nod for best actor. He also had the title role in the epic Alexander the Great (1956) and the British protest film Look Back in Anger (1959).

Burton had continued his stage performances during this period as well, working with the Old Vic and Royal Shakespeare companies in Britain and earning acclaim for his work on Broadway in 1960’s Camelot.

He was the best man at Laurence Olivier’s marriage to Joan Plowright in New York City on March 17, 1961. Both were appearing on Broadway at the time, he in Camelot and Olivier in Becket.

In the early 1960s, Burton met Taylor on the set of the multi-million dollar epic Cleopatra (1963). Though each was married at the time, the two embarked on a relationship that was met with scorn from traditional institutions that included The Vatican. The couple’s romantic tribulations and luxury-item escapades would be covered in tabloid news for years to come.

After Burton and Taylor divorced their respective spouses, the couple wed on March 15, 1964. They went on to work in 11 films together, including screen adaptations of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) and The Taming of the Shrew (1967). Woolf earned both actors Oscar nominations, for which Taylor won.

During this period, Burton appeared once again on Broadway in the 1964 staging of Hamlet, directed by Gielgud, and continued to maintain distinctive projects, garnering additional lead actor Oscar nominations for Becket (1964), The Spy Who Came in From the Cold (1965) and Anne of the Thousand Days (1969).

In 1969, Burton bought his second wife Taylor one of the world’s largest diamonds from the jeweller Cartier after losing an auction for the 69-carat, pear-shaped stone to the jeweller, which was won with a $1 million bid. Aristotle Onassis also failed in his bid to win the diamond, which he intended to give his wife Jacqueline Kennedy. The rough diamond that would yield the prized stone weighed 244 carats. Ten years later, Taylor herself auctioned off the ‘Burton-Taylor Diamond’ to fund a hospital in Botswana.

He was awarded the CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire) in the 1970 Queen’s Birthday Honours List for his services to drama. He collected this award on his 45th birthday.

Burton was a heavy drinker and remained a drinking partner of fellow actors Richard Harris and Peter O’Toole until O’Toole was forced to give up drinking after surgery in 1976. Burton himself underwent treatment for alcoholism at a clinic in America after filming The Klansman (1974).

Burton’s marriage to Taylor was noted for its volatility and storminess, with both performers battling substance addictions. The two were estranged in 1970 and divorced in 1974. They then reconciled and remarried in the autumn of 1975 in Botswana, only to divorce again the following year. Burton would marry model Suzy Hunt in 1976.

Burton said variously of Taylor: “I might run from her for a thousand years and she is still my baby child. Our love is so furious that we burn each other out…”

“…At 34, she is an extremely beautiful woman, lavishly endowed by nature with a few flaws in the masterpiece: She has an insipid double chin, her legs are too short and she has a slight potbelly. She has a wonderful bosom, though.”

“…Elizabeth has great worries about becoming a cripple because her feet sometimes have no feeling in them. She asked if I would stop loving her if she had to spend the rest of her life in a wheelchair. I told her that I didn’t care if her legs, bum and bosoms fell off and her teeth turned yellow. And she went bald. I love that woman so much sometimes that I cannot believe my luck. She has given me so much.”

She was, he said, “The most astonishingly self-contained, pulchritudinous, remote, removed, inaccessible woman I had ever seen.”

Burton continued to make films in the 1970s, including Villain (1971), Brief Encounter (1975) and Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977) and was nominated for his seventh Oscar for his role as a psychiatrist in the 1977 drama Equus.

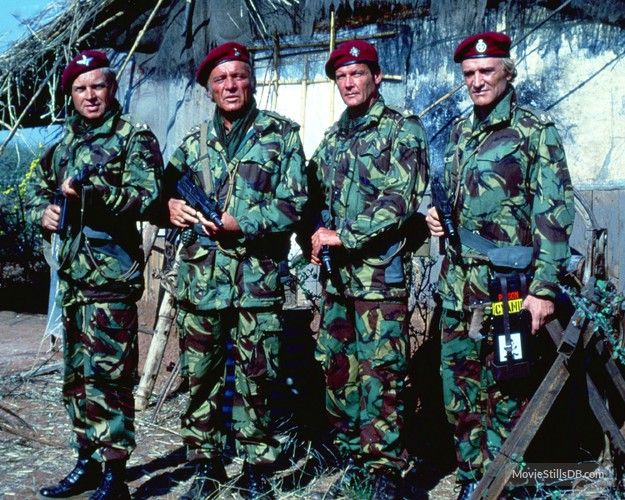

He appeared with fellow acting icons Harris and Roger Moore in The Wild Geese (1978) about mercenaries in South Africa. While the film had a modest initial run, in the ensuing years it picked up something of a cult following.

In 1980, Burton returned to the New York stage in a revival of Camelot, though his performance would later be curtailed due to the effects of medication for spinal pain; he eventually left the play to have surgery. Then, in 1983, he and Taylor returned to working together for the Noel Coward theatrical work Private Lives.

His final film was 1984, an adaptation of the George Orwell classic. Burton died on August 5, 1984, at the age of 58, from a brain hemorrhage in his Céligny, Switzerland home.

His death came less than a week before he was due to begin shooting Wild Geese II (1985). He was the only actor returning for the film and, as Colonel Allen Faulkner, would have led a team of crack mercenaries to spring aged Nazi Rudolf Hess from Spandau Prison in Berlin. The film went ahead and was dedicated to Burton’s memory.

He received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame on St David’s Day, March 1, 2013, at 6336 Hollywood Boulevard, next to Taylor’s star.

In 2005 Burton’s personal papers were deposited in Swansea University, and form a central part of the new Richard Burton Archive facility, which was formally opened in April 2010. The Richard Burton Centre for the Study of Wales takes its name from the renowned stage and film star.

Several books have chronicled Burton’s life, including The Richard Burton Diaries, published in 2012, which collects journal entries and notes kept by the actor throughout the years.

According to Melvyn Bragg’s biography, in 1959 he turned down an offer of $350,000 to star as Christ in Nicholas Ray’s remake of King of Kings (1961) – due to superstition.

A Welsh-Irish drunkard had read the palms of Burton and some friends, including Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, who were performing poetry on BBC Radio’s Third Programme and were waiting for show-time in a local pub. The drunk predicted the friends’ deaths, which in the case of Thomas, was accurate. After two other friends died within their prescribed timeframes, Burton (who had been told he would die at the age of 33) decided to take the year 1959 off so as not to tempt fate.

According to his biography And God Created Burton, he was a notorious womanizer; during his marriage to Sybil Williams he had affairs with Claire Bloom, Jean Simmons, Maggie McNamara, Lee Remick, Lana Turner and Mary Ure, and during his marriage to Elizabeth Taylor he had affairs with Geneviève Bujold, Nathalie Delon and Raquel Welch.

In November 1974, Burton had been asked to write an article about Sir Winston Churchill for The New York Times. Since Burton had just played the wartime leader in The Gathering Storm (1974), the newspaper expected a laudatory piece. Instead they were presented with a rant about Churchill the right-wing politician, about whom Burton wrote, “to know him is to hate him”.

His attack on Churchill was widely thought to have been occasioned by the fact that he was, at the time, engaged to Princess Elizabeth of Yugoslavia – a princess in exile. She blamed Churchill and other western leaders for giving away her country to the Communists at the end of World War II. Burton’s engagement to her was soon broken off.

Burton and Taylor were very close friends with the president of former Yugoslavia, Marshall Josip Broz Tito. They spent many vacations with him at his villa on the Yugoslavian Adriatic coast as well as being a frequent guest at his mansion in Belgrade. He later played his close friend in the 1972 Yugoslavian film The Battle of Sutjeska (1973).

Famous for his high intelligence and for being incredibly well-read, Burton was widely admired for his command and understanding of English poetry, which he taught for a term at Oxford University in the early 1970s.

He once got into a contest with Robert F Kennedy, whom he greatly admired, in which they tried to out-do the other by quoting William Shakespeare’s sonnets. Both were word-perfect and Burton was forced to ‘win’ the contest by quoting one of the sonnets backwards.

He was a great fan of baseball, which he followed avidly when he was in America. Burton thought Pulitzer Prize-winning baseball columnist Red Smith was a brilliant writer. Burton played softball with a team from the Broadway theatre in the 1980s, despite crippling bursitis in his shoulder.

Burton and Warren Mitchell were Royal Air Force cadets together at Oxford in 1944. In the years 1944-1947, when both were demobilized, they were stationed together at times in Canada and back in England. Later, they appeared together in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965).

Burton was a close friend of Humphrey Bogart and also fellow Welsh actor Sir Stanley Baker from childhood, providing the narration for Baker’s epic film Zulu (1964).

He had two roles in common with ‘Carry On’ star Sidney James: (1) Burton played Mark Antony in Cleopatra (1963) while James played him in Carry on Cleo (1964) and (2) Burton played King Henry VIII of England in Anne of the Thousand Days (1969) while James played him in Carry on Henry VIII (1971). In both cases, James wore the costume which had originally been worn by Burton.

Burton was once quoted as saying: “I’ve played the lot: a homosexual, a sadistic gangster, kings, princes, a saint, the lot. All that’s left is a Carry On film. My last ambition.”

Other voice work included Jeff Wayne’s musical version of The War of the Worlds, which he recorded in two afternoon sessions in New York between film-making.

In 1981 he accepted a contract reported to be worth nearly $1 million over three years to use his voice in a series of commercials for an American magazine, Geo.

His younger brother Graham Jenkins worked for the BBC and was responsible for getting Burton the job of narrating the Royal Wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana for BBC Radio on July 29, 1981.

The last word on a colourful life should go to Burton himself: “My father considered that anyone who went to chapel and didn’t drink alcohol was not to be tolerated. I grew up in that belief.

“I rather like my reputation, actually, that of a spoiled genius from the Welsh gutter, a drunk, a womanizer; it’s rather an attractive image.

“God put me on this earth to raise sheer hell. I drank too much, smoked too much and made love too much. I have achieved a sort of diabolical fame.”

RETURN TO WELSH GREATS IN PROFILE

BACK TO HOME PAGE