Terry Jones

TERRY JONES was a Welsh actor, writer, comedian, screenwriter, film director and historian, best remembered as a member of the Monty Python comedy team.

After graduating from Oxford University with a degree in English, Jones and writing partner Michael Palin (whom he met at Oxford) wrote and performed for several high-profile British comedy programmes, including Do Not Adjust Your Set and The Frost Report, before creating Monty Python’s Flying Circus with Cambridge graduates Eric Idle, John Cleese, Graham Chapman and the American animator/filmmaker Terry Gilliam.

Jones was largely responsible for the programme’s innovative, surreal structure, in which sketches flowed from one to the next without the use of punchlines.

He made his directorial debut with the film Monty Python and the Holy Grail, which he co-directed with Gilliam, and also directed the subsequent Python films Life of Brian and The Meaning of Life.

Jones co-created and co-wrote with Palin the anthology series Ripping Yarns. He also wrote an early draft of Jim Henson’s 1986 film Labyrinth, though little of his work remained in the final cut. Jones was a well-respected medieval historian, having written several books and presented television documentaries about the period, as well as a prolific children’s book author.

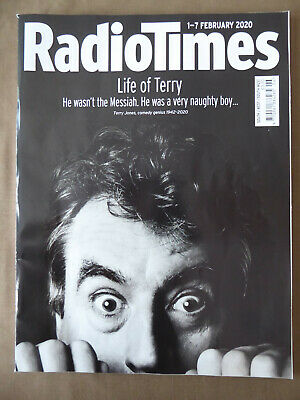

In 2016, Jones received a Lifetime Achievement award at the BAFTA Cymru Awards for his outstanding contribution to television and film. After living for several years with a degenerative aphasia, he gradually lost the ability to speak and died on January 21, 2020, from frontotemporal dementia.

Jones was born on February 1, 1942, in the seaside town of Colwyn Bay, on the north coast of Wales, the son of Dilys Louisa (Newnes), a homemaker, and Alick George Parry-Jones, a bank clerk. The family home was named Bodchwil.

As he recalled in The Pythons Autobiography by The Pythons, he was “born right bang slap in the middle of World War Two,” while his father served with the Royal Air Force in Scotland. A week after he was born, his father was posted in India as a Flight Lieutenent (Temporary).

He reunited with his father after four years, as the war ended; of their first meeting at Colwyn Bay train station he recollected: “I’d only ever been kissed by the smooth lips of a lady up until that point, so his bristly moustache was quite disturbing!”

When Jones was four and a half, the family moved to Claygate, Surrey, England. He attended Esher COE primary school, then the Royal Grammar School in Guildford, where he was school captain in the 1960–61 academic year.

He read English at St Edmund Hall, Oxford, but “strayed into history”. He became interested in the medieval period through reading Chaucer as part of his English degree. He graduated with a 2:1.

While there, he performed comedy with future Monty Python castmate Palin in the Oxford Revue. Jones was a year ahead of Palin at Oxford, and on first meeting him Palin states, “The first thing that struck me was what a nice bloke he was. He had no airs and graces. We had a similar idea of what humour could do and where it should go, mainly because we both liked characters; we both appreciated that comedy wasn’t just jokes.”

Jones appeared in Twice a Fortnight with Palin, Graeme Garden, Bill Oddie and Jonathan Lynn, as well as the television series The Complete and Utter History of Britain (1969). He appeared in Do Not Adjust Your Set (1967–69) with Palin, Idle and David Jason. He wrote for The Frost Report and several other David Frost programmes on British television.

Monty Python’s Flying Circus, the groundbreaking comedy series that made Jones and his fellow cast members international stars, first aired on BBC One in October 1969. Surreal, anarchic and bawdily irreverent, the show’s blend of live-action sketches and animated interludes mocked both broadcasting conventions and societal norms.

Of Jones’s contributions as a performer to Monty Python’s Flying Circus, his depictions of middle-aged women (or “ratbag old women” as termed by the BBC, also known as “pepper-pots” or “grannies from hell”) are among the most memorable. A range of much-loved characters also included Arthur ‘Two Sheds’ Jackson, Cardinal Biggles of the Spanish Inquisition and Mr Creosote.

Jones co-directed Monty Python and the Holy Grail with Gilliam, and was sole director on two further Monty Python movies, Life of Brian and Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life. Python fans would surely be unable to imagine the classic line, “He’s not the Messiah. He’s a very naughty boy!”, without hearing it spoken as Brian’s mother (as played in typical ‘ratbag’ style by Jones) in Life of Brian.

His later films include Erik the Viking (1989) and The Wind in the Willows (1996).

In 2008, Jones wrote the libretto for and directed the opera Evil Machines. In 2011, he was commissioned to direct and write the libretto for another opera, entitled The Doctor’s Tale.

Jones directed the 2015 comedy film Absolutely Anything, about a disillusioned schoolteacher who is given the chance to do anything he wishes by a group of aliens watching from space. The film features Simon Pegg, Kate Beckinsale, Robin Williams and the voices of the five remaining members of Monty Python. It was filmed in London during a six-week shoot.

In 2016, Jones directed Jeepers Creepers, a West End play about the life of comic Marty Feldman. It would be Jones’ last directing work before his death.

Jones wrote many books and screenplays, including comic works and more serious writing on medieval history.

A member of the Campaign for Real Ale, Jones also had interest in real ale and in 1977 co-founded the Penrhos Brewery, a microbrewery at Penrhos Court at Penrhos, Herefordshire, which ran until 1983.

Jones co-wrote Ripping Yarns with Palin. They also wrote a play, Underwood’s Finest Hour, about an obstetrician distracted during a birth by the radio broadcast of a cricket Test match, which played at the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith, in 1981. Jones also wrote numerous works for children, including Fantastic Stories, The Beast with a Thousand Teeth and a collection of comic verse called The Curse of the Vampire’s Socks.

Jones was the co-creator (with Gavin Scott) of the animated TV series Blazing Dragons (1996–1998), which parodied the Arthurian legends and Middle Ages periods. Reversing a common story convention, the series’ protagonists are anthropomorphic dragons beset by evil humans.

Jones wrote the screenplay for David Bowie’s Labyrinth (1986), although his draft went through several rewrites and several other writers before being filmed; consequently, much of the finished film was not actually written by Jones.

Jones wrote books and presented television documentaries on medieval and ancient history. His first book was Chaucer’s Knight: The Portrait of a Medieval Mercenary (1980), which offers an alternative take on Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Knight’s Tale. Chaucer’s knight is often interpreted as a paragon of Christian virtue, but Jones asserts that if one studies historical accounts of the battles the knight claims he was involved in, he can be interpreted as a typical mercenary and a potentially cold-blooded killer. He also co-wrote Who Murdered Chaucer? (2003) in which he argues that Chaucer was close to King Richard II, and that after Richard was deposed, Chaucer was persecuted to death by Thomas Arundel.

Python biographer George Perry said of Jones: “[you] speak to him on subjects as diverse as fossil fuels, or Rupert Bear, or mercenaries in the Middle Ages or Modern China … in a moment you will find yourself hopelessly out of your depth, floored by his knowledge.”

Jones’ TV series frequently challenged popular views of history. For example, in Terry Jones’ Medieval Lives (for which he received a 2004 Emmy nomination for ‘Outstanding Writing for Non-fiction Programming’), he argues that the Middle Ages was a more sophisticated period than is popularly thought, and Terry Jones’ Barbarians (2006) presents the cultural achievements of peoples conquered by the Roman Empire in a more positive light than Roman historians typically have, attributing the Sack of Rome in 410 AD to propaganda.

Jones wrote numerous columns for The Guardian, The Daily Telegraph and The Observer condemning the Iraq War. Many of these editorials were published in a paperback collection titled Terry Jones’s War on the War on Terror.

In November 2011, his book Evil Machines was launched by the online publishing house Unbound at the Adam Street Club in London. It was the first book to be published by a crowdfunding website dedicated solely to books. Jones provided significant support to Unbound as they developed their publishing concept. In February 2018, he released The Tyrant and the Squire, also with Unbound.

Jones was a member of the Poetry Society, and his poems have appeared in Poetry Review.

Jones performed with the Carnival Band and appears on their 2007 CD Ringing the Changes.

In January 2008, the Teatro São Luiz, in Lisbon, Portugal, premiered Evil Machines – a musical play, written by Jones (based on his book), with original music by Portuguese composer Luis Tinoco. Jones was invited by the Teatro São Luiz to write and direct the play, after a successful run of Contos Fantásticos, a short play based on Jones’s Fantastic Stories, also with music by Tinoco.

In January 2012 Jones announced that he was working with songwriter/producer Jim Steinman on a heavy metal version of The Nutcracker.

Apart from a cameo in Terry Gilliam’s Jabberwocky and a minor role as a drunken vicar in the BBC sitcom The Young Ones, Jones rarely appeared in work outside his own projects. From 2009 to 2011, however, he provided narration for The Legend of Dick and Dom, a CBBC fantasy series set in the Middle Ages. He also appears in two French films by Albert Dupontel: Le Créateur (1999) and Enfermés dehors (2006).

In 2009, Jones took part in the BBC Wales programme Coming Home about his Welsh family history. In July 2014, Jones reunited with the other four living Pythons to perform at 10 dates (Monty Python Live (Mostly)) at the O2 Arena in London. This was Jones’s last performance with the group prior to his aphasia diagnosis.

In October 2016, Jones received a standing ovation at the BAFTA Cymru Awards when he received a Lifetime Achievement award for his outstanding contribution to television and film. Also that year, an asteroid, 9622 Terryjones, was named in his honour.

Having overcome colon cancer in 2006, in 2015, Jones was diagnosed with primary progressive aphasia, a form of frontotemporal dementia that impairs the ability to speak and communicate. He had first given cause for concern during the Monty Python reunion show Monty Python Live (Mostly) in July 2014 because of difficulties learning his lines.

He became a campaigner for awareness of, and fundraiser for research into, dementia; and donated his brain for dementia research. By September 2016, he was no longer able to give interviews. By April 2017, he had lost the ability to say more than a few words of agreement.

Twice-married Jones died from complications of dementia on January 21, 2020, 11 days short of his 78th birthday, at his home in Highgate, North London.

Close friend Palin paid tribute to Jones: “He was far more than one of the funniest writer-performers of his generation, he was the complete Renaissance comedian — writer, director, presenter, historian, brilliant children’s author, and the warmest, most wonderful company you could wish to have.”

Gilliam described his fellow Python as a “brilliant, constantly questioning, iconoclastic, righteously argumentative and angry, but outrageously funny and generous and kind human being”.

Shane Allen, BBC controller of comedy commissioning, wrote that it was a “sad day to lose an absolute titan of British comedy” and “one of the founding fathers of the most influential and pioneering comedy ensembles of all time”.

Cleese said: “Of his many achievements, for me the greatest gift he gave us all was his direction of Life of Brian. Perfection.”

It was fitting that Jones’s last public appearance was to receive an outstanding contribution to television and film award from Bafta Cymru back in Wales. Accompanied by his son Bill, he was given a standing ovation in Cardiff after being presented with the award by Python co-star Palin in October 2016.

In later life, Jones took a keen interest in the fortunes of his home town’s Victorian theatre, becoming its patron and officially re-opened Theatr Colwyn in 2011 after a £738,000 refurbishment.

He said: “Theatr Colwyn means a lot to me because my grandfather [William Newnes] conducted the orchestra for the Colwyn Bay Operatic Society there and my mother and uncle both trod the boards on that very stage.”

Thanks to the BBC Wales programme Coming Home, he traced his family back on his father’s side to 1760, with ancestors working in lead mines and his great-grandmother a servant for the Mostyn family. His great-grandfather was a Methodist minister.

Jones’s war-time memories included being taken to a field near the family home in Dolwen Road during the war by his brother.

“He told me that a bear lived in the brook at the end of it so I ran home and didn’t dare go back,” he said. “I can also remember the thrill of seeing a tank driving up the road with these enormous searchlights.”

He met his father – a bank clerk – for the first time on the platform of Colwyn Bay railway station when he returned from India after serving with the RAF during World War Two.

He said he always felt “very Welsh” despite his mother being from Bolton and his parents moving to Claygate in Surrey when he was less than five years old.

“I bitterly didn’t want to leave and hated being transported to the London suburbs,” he recalled. “I always regretted that and was always saying ‘I’m Welsh’.”

Jones’s work was not always appreciated in every part of Wales. Monty Python’s Life Of Brian – the controversial 1979 film which Jones directed and appeared in – was banned in some towns over claims it was blasphemous for its parody of the life of Jesus Christ.

Jones called it “excellent publicity”, adding: “I think it’s popular because it is banned – that’s the real reason. But it’s wonderful to see it is popular.”

Jones and Palin attended a special 30th anniversary charity screening of the film in Aberystwyth – where it wasn’t shown until 1981 – when the town’s mayor was Sue Jones-Davies, who played Brian’s girlfriend in the film.

His 1981 children’s book Fairy Tales was adapted for the stage as Silly Kings by National Theatre Wales in 2013.

Accompanying him to the Bafta Cymru ceremony for a final public farewell and acclaim, Palin – a friend since their Oxford University days – said Jones was “very Welsh in his attitudes, his passion, his energy and inventiveness”.

RETURN TO WELSH GREATS IN PROFILE

BACK TO HOME PAGE