Barry John

BARRY JOHN was a Welsh rugby union fly-half who played during the amateur era of the sport in the 1960s and early 1970s. Regarded by many as the finest No 10 of all time, during his short playing career he was revered in Wales as ‘The King’ and feared by opposition defences.

John began his rugby career as a schoolboy playing for his local team, Cefneithin RFC, before switching to first-class west Wales team Llanelli RFC in 1964. It was while at Llanelli that John was first selected for the Wales national team, a shock selection as a replacement for David Watkins to face a touring Australian team.

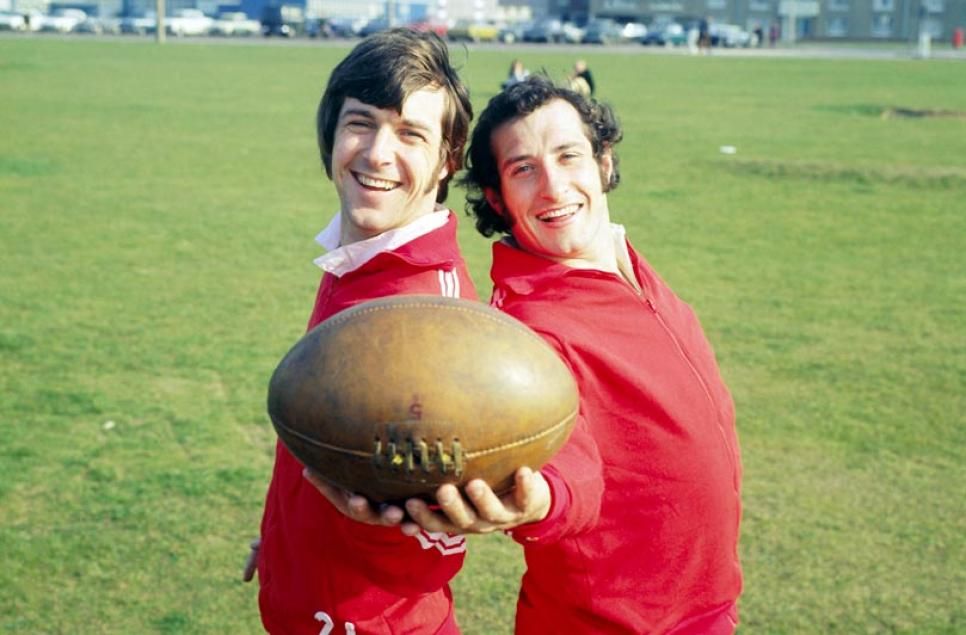

In 1967 John left Llanelli RFC for Cardiff RFC and there he formed a partnership with Gareth Edwards which became one of the most famous half-back pairings in world rugby and even spawned its own catchphrase when John famously once told the scrum-half (in Welsh) – ‘You throw it, I’ll catch it’.

From 1967, John and Edwards made an inseparable partnership with rugby selectors, being chosen to play together at all levels of the sport, for Cardiff, Wales, the Barbarians and, in 1968, for the British Lions tour of South Africa.

Asked what was the key to their enduring success, John replied: “I suppose it’s like any partnership that just clicks,” said John. “You can go to Morecambe and Wise or to Ant and Dec in modern times.

“The point is, you see, our backgrounds were almost identical. His father was a miner, my father was a miner. When I walked into his house in Gwaun-Cae-Gurwen, it was like walking into a house I had seen a million times before. I would go in and there would be a nice little bit of cake and a cup of tea his mother would have there always ready.

“Our upbringing was the same and upbringing equals values; what’s right, what’s wrong. Our values were basically the same and responsibility goes with that. There was our upbringing, our outlook towards the game and also the fact we spoke Welsh. That played a good part.”

The 1968 British Lions tour ended prematurely for John when he suffered a broken collarbone in the first Test match against the South African national team.

In 1971, the Wales national team entered what is considered their second ‘Golden Age’, with a team rich in experience and talent. John was part of the team that won the 1971 Five Nations Championship, the first time Wales had achieved a Grand Slam win since 1952.

He then cemented his reputation as one of the sport’s greatest players with his pivotal role in the British Lions’ winning tour over New Zealand in 1971. On the 1971 tour, John appeared in all four Tests, playing some of his finest rugby and finishing as the Lions’ top Test scorer.

John won 25 caps for the Wales national team and five for the Lions. Possessing excellent balance to his running, along with precision kicking, made him one of the great players of the modern era. He retired from rugby at the age of 27, as Wales’s highest points-scorer, citing the pressure of fame and expectation behind his decision.

John was born at Cefneithin, Carmarthenshire, on January 6, 1945. His early schooling was at Cefneithin Primary and there he was fortunate to receive skilled rugby teaching. The headmaster, William John Jones, and teacher Ray Williams, were both former Wales international rugby players.

After a year at Cross Hands senior centre he passed the entrance exam and was accepted into Gwendraeth Grammar School in the Gwendraeth Valley, north of Llanelli.

At 18 he left grammar school, and was awarded a place at Trinity College, Carmarthen, with ambitions of becoming a teacher. He studied physical education, junior science and horticulture.

He continued to represent Llanelli while at Trinity College and gained a reputation as a kicking fly-half with a penchant for putting over dropped goals.

He left Trinity in the summer of 1967, and took up a post as a physical education teacher at Monkton House School in Cardiff, a private school for boys between the ages of eight and 16.

John moved to Cardiff and shared a house with several other rugby players, including former Llanelli team-mate Gerald Davies. John quit his position at Monkton House when he toured South Africa in 1968 and never taught again.

On his return from Africa, John moved back to his family home at Cefneithin. He spent six weeks unemployed and during this period he considered turning to professional rugby league, almost signing for St Helens.

Following an interview with David Coleman for the BBC programme Sportsnight in which his jobless situation was discussed, John was offered a job working for Forward Trust, a finance company in Cardiff. When John quit playing rugby in 1972 he also left his job as a finance representative, signing a contract to write a weekly column and cover important matches for the Daily Express. He was also signed to take part in sport programmes presented by HTV, the Wales and west of England commercial television company.

John made a losing international debut against Australia on December 3, 1966, while still a student at Trinity College. He managed to gain a measure of revenge over Australia just over a month later when the Wallabies lost 11-0 to Llanelli at Stradey Park, John himself scoring a try and a dropped goal.

In his early years with Wales, he played in an inconsistent side that did not bring out the best of his mercurial talent. It was during this time that he left Llanelli and joined Cardiff and first began playing alongside Edwards, sowing the seed for one of the most famous half-back partnerships in rugby history.

John was at his most potent when awaiting the fearsome long pass of Edwards. He was able to vary his game instantly, either taking on the first-phase defence with his footwork or waiting for the ball to arrive in his hands before unleashing his centres into space or fooling the defence with his deft kicking.

Following two years in the Welsh set-up, John was selected for the 1968 Lions tour to South Africa, but a broken collar bone ended his tour after only the first Test.

Before the end of the season, John took part in his one and only seven-a-side tournament for Cardiff when he participated in the 1969 Snelling Sevens tournament. Cardiff progressed to the final, where they succeeded in beating John’s former club Llanelli. As well as the title, John won the Bill Everson Player of the Tournament award.

His return to international rugby from injury was as part of a Wales team that dominated northern hemisphere rugby during the 1970s. While the team was filled with stars like Edwards, JPR Williams, Gerald Davies and John Dawes to name but a few, attention was lavished on John by Welsh fans.

The 1971 Five Nations Championship was a new dawn for Welsh rugby, Wales achieving their first Grand Slam since 1952. John and Edwards played in all four games, starting with an easy win over England. Wales won 22–6, with John scoring six points from two dropped goals.

The second game of the Championship, played against Scotland, was a close encounter, won by Wales 19–18 thanks to a late Gerald Davies try converted by John Taylor. John scored eight of Wales’s points, with a try, penalty goal and a conversion; missing only his trademark drop goal to complete a full house of scores.

John surpassed his Scotland tally in the next match, a home game against Ireland, scoring 11 points with a dropped goal, conversion and two penalty goals. Seen as one of Wales’s more accomplished victories, the 23–0 win gave the team a Triple Crown title and set up a Grand Slam encounter with France.

Despite the low score, the 9–5 win over France at Stade Colombes on March 27 was a match of the highest quality. Edwards and John scored all the points in the encounter, Edwards with a try, John a try and a penalty goal.

John was selected for the Lions tour to New Zealand later that year and it was on this tour, under the management of Doug Smith and the coaching of Carwyn James (also from Cefneithin), that the Wales outside-half shone brightest of all. His display of tactical kicking in the first Test, terrorising All Black full-back Fergie McCormick, was a masterclass that set in motion a famous series victory.

This performance was followed by one of his most memorable tries in the third Test at Wellington. John dummied a drop-goal before ghosting through the All Blacks’ defence, stepping inside the final tackler and dotting down under the posts in front of a stunned crowd. John left New Zealand having scored 30 of the Lions’ 48 points over the four Test matches, orchestrating a 2-1 series victory and cementing his reputation as one of the game’s greatest players.

John’s final international was at home to France in the 1972 Five Nations Championship. He successfully converted four penalty goals in a 20–6 victory to Wales, and in scoring his final penalty surpassed the Wales international points-scoring record of Jack Bancroft set nearly 60 years earlier.

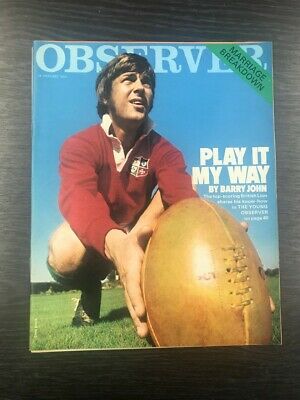

Only a year after returning from the Lions tour, John retired from rugby. At 27 he was still at the height of his powers, but had become weary of the “goldfish bowl” of Welsh rugby.

ESPN’s Huw Baines, writing in 2008, touched upon a piece of rugby folklore that was said to have hastened John’s decision to hang up his boots. “The final straw came for him when a young girl curtsied to ‘The King’ as he opened a bank. Describing what he called ‘the monster of fame’ as his reason for leaving his rugby career behind, John vanished from the public eye altogether. He was followed [in the Wales No 10 shirt] by another great fly-half, Phil Bennett, but John’s ability to do the unexpected and the majesty of his control meant that he was a one-off in the eyes of Welsh fans and the wider rugby community.”

His 25 caps for Wales resulted in 90 points scored, from five tries, nine conversions, 13 penalties and eight dropped goals. His British Lions career added a further 30 international points. For Cardiff he played five seasons, playing 93 matches, during which he scored 24 tries and 30 dropped goals. His dropped-goal total for Cardiff was the club’s second highest, level with Wilf Wooller, but short of Percy Bush’s tally of 35. He also played for the Barbarians, in partnership with Edwards, against New Zealand in 1967 and South Africa in 1970.

Edwards, in his 1978 autobiography, when describing John, wrote: “He had this marvellous easiness in the mind, reducing problems to their simplest form, backing his own talent all the time. One success on the field bred another and soon he gave off a cool superiority which spread to others in the side. Physically he was perfectly made for the job, good and strong from the hips down and firm but slender from the waist to the shoulders.”

The authors of the official history of the Welsh Rugby Union, David Smith and Gareth Williams, wrote of him: “John ran in another dimension of time and space. His opponents ran into the glass walls which covered his escape routes from their bewildered clutches. He left mouths, and back rows, agape.”

Gerald Davies, who played with John for Wales and the British Lions, in his 1971 autobiography when contrasting Edwards’ and John’s different temperaments described Edwards as “fiery and impulsive”, but John was “…fairer, aloof and apart. Whilst the hustle and bustle went on around him he could divorce himself from it all; he kept his emotions in check and a careful rein on the surrounding action. The game would go according to his will and no-one else’s…”

Rodney Webb, who represented England between 1967 and 1972, is quoted as saying: “Barry John’s punting was phenomenal. He could drop the ball on a sixpence and he could do it every time”. Webb, who developed the modern rugby ball, believes that John can not be compared to modern kickers because “the modern ball is coated in a laminate, has dimpled surfaces, unobtrusive lacing and multi panels. In the ‘Seventies the balls soaked up water, swerved all over the place and were placed in the mud and slime when kicking for goal”.

Describing playing conditions in Wales back then, John said: “The old word was quagmire. People playing now wouldn’t know what it was all about. You used to run on to the pitch and there would be puddles all over the place and there would be the colours of the rainbow because that’s where the petrol had dropped from the tractors trying to flatten it out. If you had a mouthful of that, you were in trouble!”

John came third in the 1971 BBC Sports Personality of the Year Award, beaten by winner Princess Anne and runner-up George Best. John was one of the inaugural inductees of the International Rugby Hall of Fame in 1997 and in 1999 was inducted into the Welsh Sports Hall of Fame. In 2015 John was inducted into the World Rugby Hall of Fame.

However, in 2009, he decided to sell his rugby memorabilia, including his Wales caps, stating that he felt no nostalgia towards the items, and the honour of playing for Wales was all that mattered.

John died peacefully at the University Hospital of Wales in February 2024, aged 79, surrounded by his wife and four children.

BACK TO HOME PAGE