Dylan Thomas

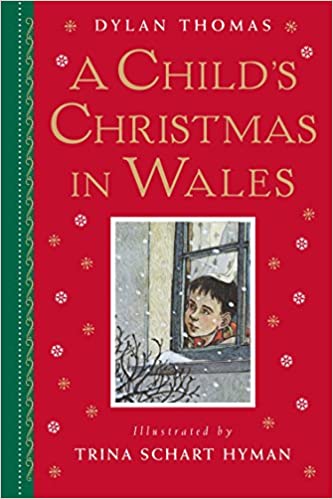

DYLAN THOMAS was a Welsh poet and writer whose works include the poems Do not go gentle into that good night and And death shall have no dominion; the ‘play for voices’ Under Milk Wood; and stories and radio broadcasts such as A Child’s Christmas in Wales and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog.

He became widely popular in his lifetime and remained so after his premature death at the age of 39 in New York City. By then he had acquired a reputation, which he had encouraged, as a “roistering, drunken and doomed poet”.

Thomas was born at Cwmdonkin Drive, Swansea, on October 27, 1914. An undistinguished pupil, he left school at 16 and became a journalist for a short time. Many of his works appeared in print while he was still a teenager, and the publication in 1934 of Light breaks where no sun shines caught the attention of the literary world.

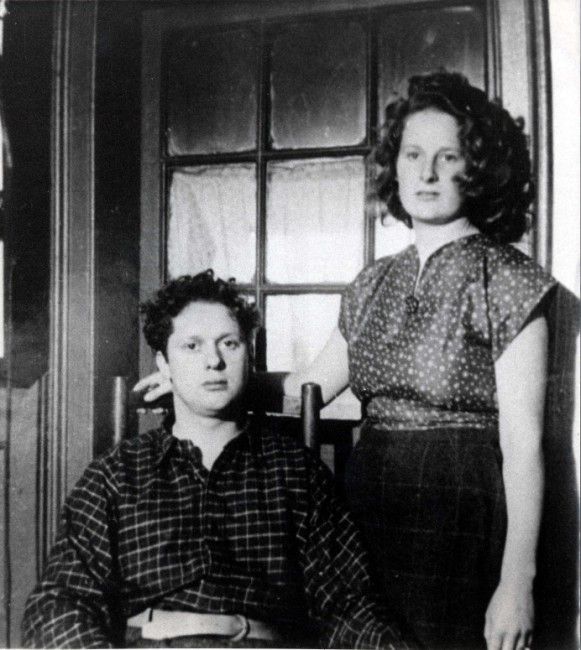

While living in London, Thomas met Caitlin Macnamara, whom he married in 1937. In 1938, they moved to the Welsh fishing village of Laugharne where, from 1949, they settled permanently and brought up their three children.

Thomas came to be appreciated as a popular poet during his lifetime, though he found earning a living as a writer difficult. He began augmenting his income with reading tours and radio broadcasts. His radio recordings for the BBC during the late 1940s brought him to the public’s attention, and he was frequently used by the BBC as an accessible voice of the literary scene.

Thomas first travelled to the United States in the 1950s. His readings there brought him a degree of fame, while his erratic behaviour and drinking worsened. His time in the United States cemented his legend, however, and he went on to record to vinyl such works as A Child’s Christmas in Wales.

During his fourth trip to New York in 1953, Thomas became gravely ill and fell into a coma, from which he never recovered. He died on November 9, 1953. His body was returned to Wales, where he was interred at the churchyard of St Martin’s in Laugharne on November 25, 1953.

Although Thomas wrote exclusively in the English language, he has been acknowledged as one of the most important Welsh poets of the 20th Century. He is noted for his original, rhythmic and ingenious use of words and imagery. His position as one of the great modern poets has been much discussed, and he remains popular with the public.

Thomas’s father chose the name Dylan after Dylan ail Don, a character in The Mabinogion.

Thomas had bronchitis and asthma in childhood and struggled with these throughout his life. His formal education began at Mrs Hole’s dame school, a private school on Mirador Crescent, a few streets away from his home. He described his experience there in Quite Early One Morning:

“Never was there such a dame school as ours, so firm and kind and smelling of galoshes, with the sweet and fumbled music of the piano lessons drifting down from upstairs to the lonely schoolroom, where only the sometimes tearful wicked sat over undone sums, or to repent a little crime – the pulling of a girl’s hair during geography, the sly shin kick under the table during English literature.”

In October 1925, Thomas enrolled at Swansea Grammar School for boys, in Mount Pleasant, where his father taught English. He was an undistinguished pupil who shied away from school, preferring reading. In his first year one of his poems was published in the school’s magazine, and before he left he became its editor.

During his final school years he began writing poetry in notebooks; the first poem, dated 27 April (1930), is entitled Osiris, come to Isis. In June 1928 Thomas won the school’s mile race, held at St. Helen’s Ground; he carried a newspaper photograph of his victory with him until his death.

In 1931, when he was 16, Thomas left school to become a reporter for the South Wales Daily Post and later worked as a freelance journalist for several years, during which time he remained at Cwmdonkin Drive and amassed 200 poems in four books between 1930 and 1934. Of the 90 poems he published, half were written during these years.

In his free time, he joined the amateur dramatic group at the Little Theatre in Mumbles, visited the cinema in Uplands, took walks along Swansea Bay and frequented Swansea’s pubs, especially the Antelope and the Mermaid Hotels in Mumbles.

In the Kardomah Café, close to the newspaper office in Castle Street, he met his creative contemporaries, including his friend the poet Vernon Watkins. The group of writers, musicians and artists became known as ‘The Kardomah Gang’.

Thomas was a teenager when many of the poems for which he became famous were published: And death shall have no dominion, Before I Knocked and The Force That Through the Green Fuse Drives the Flower. And death shall have no dominion appeared in the New English Weekly in May 1933.

When Light breaks where no sun shines appeared in The Listener in 1934, it caught the attention of three senior figures in literary London, TS Eliot, Geoffrey Grigson and Stephen Spender. They contacted Thomas and his first poetry volume, 18 Poems, was published in December 1934.

The volume was critically acclaimed and won a contest run by the Sunday Referee, netting him new admirers from the London poetry world, including Edith Sitwell and Edwin Muir. The anthology was published by Fortune Press, in part a vanity publisher that did not pay its writers and expected them to buy a certain number of copies themselves.

In September 1935, Thomas met Vernon Watkins, thus beginning a lifelong friendship. Thomas introduced Watkins, working at Lloyds Bank at the time, to his friends, by now known as The Kardomah Gang. In those days, Thomas used to frequent the cinema on Mondays with Tom Warner who, like Watkins, had recently suffered a nervous breakdown.

In December 1935 Thomas contributed the poem The Hand That Signed the Paper to Issue 18 of the bi-monthly New Verse. In 1936, his next collection, Twenty-five Poems, published by JM Dent, also received much critical praise. In all, he wrote half his poems while living at Cwmdonkin Drive before moving to London. It was the time that Thomas’s reputation for heavy drinking developed.

In early 1936, Thomas met Caitlin Macnamara (1913–94), a 22-year-old blonde-haired, blue-eyed dancer of Irish and French descent. She had run away from home, intent on making a career in dance, and aged 18 joined the chorus line at the London Palladium.

They married at the register office in Penzance, Cornwall, on July 11, 1937. In early 1938 they moved to Wales, renting a cottage in the village of Laugharne, Carmarthenshire. Their first child, Llewelyn Edouard, was born on January 30, 1939.

During the politically-charged atmosphere of the 1930s, Thomas’s sympathies were very much with the radical left, to the point of holding close links with the communists, as well as decidedly pacifist and anti-fascist. He was a supporter of the left-wing No More War Movement and boasted about participating in demonstrations against the British Union of Fascists.

In 1939, a collection of 16 poems and seven of the 20 short stories published by Thomas in magazines since 1934, appeared as The Map of Love. Ten stories in his next book, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog (1940), were based less on lavish fantasy than those in The Map of Love and more on real-life romances featuring himself in Wales.

Sales of both books were poor, resulting in Thomas living on meagre fees from writing and reviewing. At this time he borrowed heavily from friends and acquaintances. Hounded by creditors, Thomas and his family left Laugharne in July 1940 and moved to the home of critic John Davenport in Marshfield, Gloucestershire. There Thomas collaborated with Davenport on the satire The Death of the King’s Canary, though due to fears of libel the work was not published until 1976.

At the outset of the Second World War, Thomas was worried about conscription. Saddened to see his friends going on active service, he continued drinking and struggled to support his family. He wrote begging letters to random literary figures asking for support, a plan he hoped would provide a long-term regular income. Thomas supplemented his income by writing scripts for the BBC, which not only gave him additional earnings but also provided evidence that he was engaged in essential war work.

In February 1941, Swansea was bombed by the Luftwaffe in a “three nights’ blitz”. Castle Street was one of many streets that suffered badly; rows of shops, including the Kardomah Café, were destroyed. Thomas walked through the bombed-out shell of the town centre with his friend Bert Trick. Upset at the sight, he concluded: “Our Swansea is dead”. Soon after the bombing raids, Thomas wrote a radio play, Return Journey Home, which described the café as being “razed to the snow”. The play was first broadcast on 15 June 1947. The Kardomah Café reopened on Portland Street after the war.

In May 1941, Thomas and Caitlin left their son with his grandmother at Blashford and moved to London. Thomas hoped to find employment in the film industry and wrote to the director of the films division of the Ministry of Information (MOI). After being rebuffed, he found work with Strand Films, providing him with his first regular income since the Daily Post.

Strand produced films for the MOI; Thomas scripted at least five films in 1942, This Is Colour (a history of the British dyeing industry) and New Towns For Old (on post-war reconstruction). These Are The Men (1943) was a more ambitious piece in which Thomas’s verse accompanies Leni Riefenstahl’s footage of an early Nuremberg Rally. Conquest of a Germ (1944) explored the use of early antibiotics in the fight against pneumonia and tuberculosis. Our Country (1945) was a romantic tour of Britain set to Thomas’s poetry.

In early 1943, Thomas began a relationship with Pamela Glendower; one of several affairs he had during his marriage. The affairs either ran out of steam or were halted after Caitlin discovered his infidelity. In March 1943 Caitlin gave birth to a daughter, Aeronwy, in London. They lived in a run-down studio in Chelsea.

In 1944, with the threat of German flying bombs on London, Thomas moved to the family cottage at Blaen Cwm near Llangain, where Thomas resumed writing poetry, completing Holy Spring and Vision and Prayer. In September, Thomas and Caitlin moved to New Quay in Cardiganshire (Ceredigion), which inspired Thomas to pen the radio piece Quite Early One Morning, a sketch for his later work, Under Milk Wood. Of the poetry written at this time, of note is Fern Hill, believed to have been started while living in New Quay, but completed at Blaen Cwm in mid-1945.

Although Thomas had previously written for the BBC, it was a minor and intermittent source of income. In 1943 he wrote and recorded a 15-minute talk entitled Reminiscences of Childhood for the Welsh BBC. In December 1944 he recorded Quite Early One Morning (produced by Aneirin Talfan Davies, again for the Welsh BBC) but when Davies offered it for national broadcast BBC London turned it down.

On August 31, 1945 the BBC Home Service broadcast Quite Early One Morning and in the three years beginning October 1945, Thomas made over a hundred broadcasts for the corporation. Thomas was employed not only for his poetry readings, but for discussions and critiques.

By late September 1945 the Thomases had left Wales and were living with various friends in London. The publication of Deaths and Entrances in 1946 was a turning point for Thomas. Poet and critic Walter J Turner commented in The Spectator, “This book alone, in my opinion, ranks him as a major poet”.

In the second half of 1945 Thomas began reading for the BBC Radio programme, Book of Verse, broadcast weekly to the Far East. This provided Thomas with a regular income and brought him into contact with Louis MacNeice, a congenial drinking companion whose advice Thomas cherished.

On September 29, 1946, the BBC began transmitting the Third Programme, a high-culture network which provided opportunities for Thomas. He appeared in the play Comus for the Third Programme, the day after the network launched, and his rich, sonorous voice led to character parts, including the lead in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon and Satan in an adaptation of Paradise Lost.

Thomas remained a popular guest on radio talk shows for the BBC, who regarded him as “useful should a younger generation poet be needed”. He had an uneasy relationship with BBC management and a staff job was never an option, with drinking cited as the problem. Despite this, Thomas became a familiar radio voice.

Thomas visited the home of historian AJP Taylor in Disley. Although Taylor disliked him intensely, he stayed for a month, drinking “on a monumental scale”, up to 15 or 20 pints of beer a day. In late 1946 Thomas turned up at the Taylors’ again, this time homeless and with Caitlin. Margaret Taylor let them take up residence in the garden summerhouse.

After a three-month holiday in Italy, Thomas and family moved, in September 1947, into the Manor House in South Leigh, just west of Oxford. He continued with his work for the BBC, completed a number of film scripts and worked further on his ideas for Under Milk Wood. In May 1949 Thomas and his family moved to his final home, the Boat House at Laugharne, purchased for him at a cost of £2,500 in April 1949 by Margaret Taylor.

Thomas acquired a garage a hundred yards from the house on a cliff ledge which he turned into his writing shed, and where he wrote several of his most acclaimed poems. Just before moving into there, Thomas rented Pelican House opposite his regular drinking den, Brown’s Hotel, for his parents who lived there from 1949 until 1953. It was there that his father died and the funeral was held. Caitlin gave birth to their third child, a boy named Colm Garan Hart, on July 25, 1949.

American poet John Brinnin invited Thomas to New York, where in 1950 they embarked on a lucrative three-month tour of arts centres and campuses. The tour, which began in front of an audience of a thousand at the Kaufmann Auditorium of the Poetry Centre in New York, took in about 40 venues.

During the tour Thomas was invited to many parties and functions and on several occasions became drunk – going out of his way to shock people – and was a difficult guest. Thomas drank before some of his readings, though it is argued he may have pretended to be more affected by it than he actually was.

The writer Elizabeth Hardwick recalled how intoxicating a performer he was and how the tension would build before a performance: “Would he arrive only to break down on the stage? Would some dismaying scene take place at the faculty party? Would he be offensive, violent, obscene?” Caitlin said in her memoir, “Nobody ever needed encouragement less, and he was drowned in it.”

On returning to Britain, Thomas began work on two further poems, In the white giant’s thigh, which he read on the Third Programme in September 1950, and the incomplete In country heaven. 1950 is also believed to be the year that he began work on Under Milk Wood, under the working title ‘The Town That Was Mad’. The task of seeing this work through to production was assigned to the BBC’s Douglas Cleverdon, who had been responsible for casting Thomas in Paradise Lost.

Despite Cleverdon’s urges, the script slipped from Thomas’s priorities and in early 1951 he took a trip to Iran to work on a film for the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. The film was never made, with Thomas returning to Wales in February, though his time there allowed him to provide a few minutes of material for a BBC documentary entitled ‘Persian Oil’.

Early that year Thomas wrote two poems, which Thomas’s principal biographer, Paul Ferris, describes as “unusually blunt”; the ribald Lament and an ode, in the form of a villanelle, to his dying father Do not go gentle into that good night.

Despite a range of wealthy patrons, including Margaret Taylor, Princess Marguerite Caetani and Marged Howard-Stepney, Thomas was still in financial difficulty, and he wrote several begging letters to notable literary figures including the likes of TS Eliot.

Taylor was not keen on Thomas taking another trip to the United States, and thought that if Thomas had a permanent address in London he would be able to gain steady work there. She bought a property, 54 Delancey Street, in Camden Town, and in late 1951 Thomas and Caitlin lived in the basement flat. Thomas would describe the flat as his “London house of horror” and did not return there after his 1952 tour of America.

Thomas undertook a second tour of the United States in 1952, this time with Caitlin – after she had discovered he had been unfaithful on his earlier trip. They drank heavily, and Thomas began to suffer with gout and lung problems. The second tour was the most intensive of the four, taking in 46 engagements.

The trip also resulted in Thomas recording his first poetry to vinyl, which Caedmon Records released in America later that year. One of his works recorded during this time, A Child’s Christmas in Wales, became his most popular prose work in America. The original 1952 recording of A Child’s Christmas in Wales was a 2008 selection for the United States National Recording Registry, stating that it is “credited with launching the audiobook industry in the United States”.

In April 1953 Thomas returned alone for a third tour of America. He performed a “work in progress” version of Under Milk Wood, solo, for the first time at Harvard University on May 3. A week later the work was performed with a full cast at the Poetry Centre in New York. He met the deadline only after being locked in a room by Brinnin’s assistant, Liz Reitell, and was still editing the script on the afternoon of the performance; its last lines were handed to the actors as they put on their make-up.

During this penultimate tour, Thomas met the composer Igor Stravinsky who had become an admirer after having been introduced to his poetry by WH Auden. They had discussions about collaborating on a “musical theatrical work” for which Thomas would provide the libretto on the theme of “the rediscovery of love and language in what might be left after the world after the bomb.”

The shock of Thomas’s death later in the year moved Stravinsky to compose his In Memoriam Dylan Thomas for tenor, string quartet, and four trombones. The first performance in Los Angeles in 1954 was introduced with a tribute to Thomas from Aldous Huxley.

Thomas spent the last nine or 10 days of his third tour in New York mostly in the company of Reitell, with whom he had an affair. During this time Thomas fractured his arm falling down a flight of stairs when drunk. Reitell’s doctor, Milton Feltenstein, put his arm in plaster and treated him for gout and gastritis.

After returning home, Thomas worked on Under Milk Wood in Wales before sending the original manuscript to Douglas Cleverdon on October 15, 1953. It was copied and returned to Thomas, who lost it in a pub in London and required a duplicate to take to America. Thomas flew to the States on October 19, 1953 for what would be his final tour.

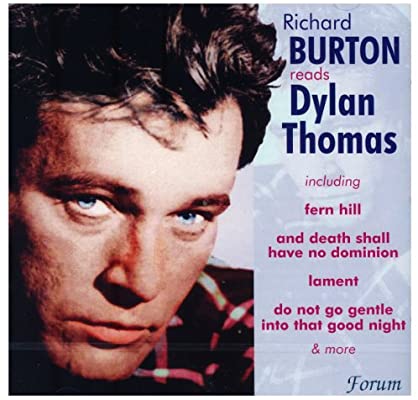

He died in New York before the BBC could record Under Milk Wood. Richard Burton starred in the first broadcast in 1954, and was joined by Elizabeth Taylor in a subsequent film. In 1954 the play won the Prix Italia for literary or dramatic programmes.

Thomas’s last collection, Collected Poems, 1934–1952, published when he was 38, won the Foyle poetry prize. Reviewing the volume, critic Philip Toynbee declared that “Thomas is the greatest living poet in the English language”. Thomas’s father died from pneumonia just before Christmas 1952. In the first few months of 1953 his sister died from liver cancer, one of his patrons took an overdose of sleeping pills, three friends died at an early age and Caitlin had an abortion.

And death shall have no dominion.

Dead men naked they shall be one

With the man in the wind and the west moon;

When their bones are picked clean and the clean bones gone,

They shall have stars at elbow and foot;

Though they go mad they shall be sane,

Though they sink through the sea they shall rise again

Though lovers be lost love shall not;

And death shall have no dominion.

From And death shall have no dominion,

Twenty-five Poems (1936)

Thomas arrived in New York on October 20, 1953 to undertake another tour of poetry-reading and talks, organised by John Brinnin. He was in a melancholy mood about the trip and his health was poor.

It is believed that Thomas had been suffering from bronchitis and pneumonia, as well as emphysema, immediately before his death. In their 2004 book Dylan Remembered 1935–1953, Volume 2, David N Thomas and Dr Simon Barton disclose that Thomas was found to have pneumonia when he was admitted to hospital in a coma. Thomas died at noon on November 9, having never recovered from his coma.

At the post-mortem, the pathologist found three causes of death – pneumonia, brain swelling and a fatty liver. Despite the poet’s heavy drinking, his liver showed no sign of cirrhosis.

The publication of John Brinnin’s 1955 biography Dylan Thomas in America cemented Thomas’s legacy as the “doomed poet”; Brinnin focuses on Thomas’s last few years and paints a picture of him as a drunk and a philanderer. Later biographies have criticised Brinnin’s view, especially his coverage of Thomas’s death.

Caitlin Thomas’s autobiographies, Caitlin Thomas – Leftover Life to Kill (1957) and My Life with Dylan Thomas: Double Drink Story (1997), describe the effects of alcohol on the poet and on their relationship. “Ours was not only a love story, it was a drink story, because without alcohol it would never had got on its rocking feet”, she wrote, and “The bar was our altar.”

Thomas’s refusal to align with any literary group or movement has made him and his work difficult to categorise. Thomas is viewed as part of the modernism and romanticism movements. Elder Olson, in his 1954 critical study of Thomas’s poetry, wrote “… a further characteristic which distinguished Thomas’s work from that of other poets. It was unclassifiable.”

Thomas derived his closely woven, sometimes self-contradictory images from the Bible, Welsh folklore, preaching, and Sigmund Freud. Explaining the source of his imagery, Thomas wrote in a letter to Glyn Jones: “My own obscurity is quite an unfashionable one, based, as it is, on a preconceived symbolism derived (I’m afraid all this sounds wooly and pretentious) from the cosmic significance of the human anatomy”.

Thomas’s early poetry was noted for its verbal density, alliteration, sprung rhythm and internal rhyme, and he was described by some critics as having been influenced by the English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins. This is attributed to Hopkins, who taught himself Welsh and who used sprung verse, bringing some features of Welsh poetic metre into his work. One poet Thomas greatly admired, and who is regarded as an influence, was Thomas Hardy.

Other poets from whom critics believe Thomas drew influence include James Joyce, Arthur Rimbaud and DH Lawrence. Although Thomas described himself as the “Rimbaud of Cwmdonkin Drive”, he stated that the phrase “Swansea’s Rimbaud” was coined by poet Roy Campbell. Critics have explored the connection between the creation of Thomas’s mythological pasts into his works such as The Orchards, which Ann Elizabeth Mayer believes reflects the Welsh myths of The Mabinogion.

Thomas’s poetry is notable for its musicality, most clear in Fern Hill, In Country Sleep, Ballad of the Long-legged Bait and In the White Giant’s Thigh from Under Milk Wood.

Thomas once confided that the poems which had most influenced him were Mother Goose rhymes which his parents taught him when he was a child:

“I should say I wanted to write poetry in the beginning because I had fallen in love with words. The first poems I knew were nursery rhymes and before I could read them for myself I had come to love the words of them. The words alone. What the words stood for was of a very secondary importance.”

Thomas was an accomplished writer of prose poetry, with collections such as Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog (1940) and Quite Early One Morning (1954) showing he was capable of writing moving short stories. His first published prose work was After the Fair, printed in The New English Weekly on March 15, 1934. Jacob Korg believes that Thomas’s fiction work can be classified into two main bodies, vigorous fantasies in a poetic style and, after 1939, more straightforward narratives.

Thomas disliked being regarded as a provincial poet, and decried any notion of ‘Welshness’ in his poetry. When he wrote to Stephen Spender in 1952, thanking him for a review of his Collected Poems, he added “Oh, & I forgot. I’m not influenced by Welsh bardic poetry. I can’t read Welsh.”

Despite this, his work was rooted in the geography of Wales. Thomas acknowledged that he returned to Wales when he had difficulty writing, and John Ackerman argues that “His inspiration and imagination were rooted in his Welsh background”.

Caitlin Thomas wrote that he worked “in a fanatically narrow groove, although there was nothing narrow about the depth and understanding of his feelings. The groove of direct hereditary descent in the land of his birth, which he never in thought, and hardly in body, moved out of.”

Head of Programmes Wales at the BBC, Aneirin Talfan Davies, who commissioned several of Thomas’s early radio talks, believed that the poet’s “whole attitude is that of the medieval bards.” Kenneth O Morgan counter-argues that it is a “difficult enterprise” to find traces of cynghanedd (consonant harmony) or cerdd dafod (tongue-craft) in Thomas’s poetry. Instead he believes his work, especially his earlier more autobiographical poems, are rooted in a changing country which echoes the Welshness of the past and the Anglicisation of the new industrial nation: “rural and urban, chapel-going and profane, Welsh and English, Unforgiving and deeply compassionate.”

Fellow poet and critic Glyn Jones believed that any traces of cynghanedd in Thomas’s work were accidental, although he felt Thomas consciously employed one element of Welsh metrics; that of counting syllables per line instead of feet. Constantine Fitzgibbon, Thomas’s first in-depth biographer, wrote “No major English poet has ever been as Welsh as Dylan”.

Although Thomas had a deep connection with Wales, he disliked Welsh nationalism. He once wrote, “Land of my fathers, and my fathers can keep it”. Glyn Jones believed that he and Thomas’s friendship cooled in the later years as he had not ‘rejected enough’ of the elements that Thomas disliked – “Welsh nationalism and a sort of hill farm morality”. Apologetically, in a letter to Keidrych Rhys, editor of literary magazine Wales, Thomas’s father wrote that he was “afraid Dylan isn’t much of a Welshman”. Though FitzGibbon asserts that Thomas’s negativity towards Welsh nationalism was fostered by his father’s hostility towards the Welsh language.

Thomas’s work and stature as a poet have been much debated by critics and biographers since his death. Critical studies have been clouded by Thomas’s personality and mythology, especially his drunken persona and death in New York.

Many critics have argued that Thomas’s work is too narrow and that he suffers from verbal extravagance. Those that have championed his work have found the criticism baffling. Robert Lowell wrote in 1947, “Nothing could be more wrongheaded than the English disputes about Dylan Thomas’s greatness … He is a dazzling obscure writer who can be enjoyed without understanding.”

Philip Larkin in a letter to Kingsley Amis in 1948, wrote that “no one can ‘stick words into us like pins’… like he [Thomas] can”. Amis was far harsher, finding little of merit in his work. David Lodge, writing about The Movement in 1981 stated: “Dylan Thomas was made to stand for everything they detest, verbal obscurity, metaphysical pretentiousness and romantic rhapsodizing”.

Despite criticism by sections of academia, Thomas’s work has been embraced by readers more so than many of his contemporaries and is one of the few modern poets whose name is recognised by the general public.

In 2009, over 18,000 votes were cast in a BBC poll to find the UK’s favourite poet; Thomas was placed 10th. Several of his poems have passed into the cultural mainstream and his work has been used by authors, musicians and film and television writers.

John Goodby cites that despite a brief period during the 1960s when Thomas was considered a cultural icon, that the poet has been marginalized in critical circles due to his exuberance, in both life and work, and his refusal to know his place.

In Swansea’s maritime quarter are the Dylan Thomas Theatre, home of the Swansea Little Theatre of which Thomas was once a member, and the former Guildhall built in 1825 and now occupied by the Dylan Thomas Centre, a literature centre, where exhibitions and lectures are held and setting for the annual Dylan Thomas Festival.

Outside the centre stands a bronze statue of Thomas, by John Doubleday. Another monument to Thomas stands in Cwmdonkin Park, one of his favourite childhood haunts, close to his birthplace. The memorial is a small rock in an enclosed garden within the park, cut and inscribed by the late sculptor Ronald Cour with the closing lines from Fern Hill.

Oh as I was young and easy in the mercy of his means

Time held me green and dying

Though I sang in my chains like the sea.

Thomas’s home in Laugharne, the Boathouse, is a museum run by Carmarthenshire County Council. Thomas’s writing shed is also preserved.

In 2004, the Dylan Thomas Prize was created in his honour, awarded to the best published writer in English under the age of 30. In 2005, the Dylan Thomas Screenplay Award was established. The prize, administered by the Dylan Thomas Centre, is awarded at the annual Swansea Bay Film Festival.

In 1982, a plaque was unveiled in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey. The plaque is also inscribed with the last two lines of Fern Hill.

In 2014, to celebrate the centenary of Thomas’s birth, the British Council Wales undertook a year-long programme of cultural and educational works. Highlights included a touring replica of Thomas’s work shed, Sir Peter Blake’s exhibition of illustrations based on Under Milk Wood and a 36-hour marathon of readings, which included Michael Sheen and Sir Ian McKellen performing Thomas’s work. The Royal Patron of The Dylan Thomas 100 Festival was Charles, Prince of Wales, who made a recording of Fern Hill for the event.

Posthumous film adaptations

1972: Under Milk Wood, starring Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, and Peter O’Toole

1987: A Child’s Christmas in Wales, directed by Don McBrearty

1992: Rebecca’s Daughters, starring Peter O’Toole and Joely Richardson

1996: Independence Day. Before the attack, the President paraphrases Thomas’s “do not go gentle into that good night”.

2007: Dylan Thomas: A War Films Anthology.

2009: Nadolig Plentyn yng Nghymru/A Child’s Christmas in Wales, 2009 BAFTA Best Short Film, animation, soundtrack in Welsh and English.

2014: Set Fire to the Stars, with Thomas portrayed by Celyn Jones and John Brinnin by Elijah Wood.

2014: Under Milk Wood BBC, starring Charlotte Church, Tom Jones, Griff Rhys-Jones and Michael Sheen.

2014: Interstellar. The poem is featured throughout the film as a recurring theme regarding the perseverance of humanity.

2016: Dominion, written and directed by Steven Bernstein, examines the final hours of Thomas (Rhys Ifans).

BACK TO HOME PAGE