Ivor Novello

IVOR NOVELLO was a Cardiff-born composer and actor who became one of the most popular British entertainers – from silent films through to ‘talkies’ and long-running stage shows – of the first half of the 20th Century.

He was born David Ivor Davies on January 15, 1893, into a musical family, his mother Clara Novello Davies being an internationally-known singing teacher and choral conductor. As a boy, Novello was a singer in the Welsh Eisteddfod and his first successes were as a songwriter.

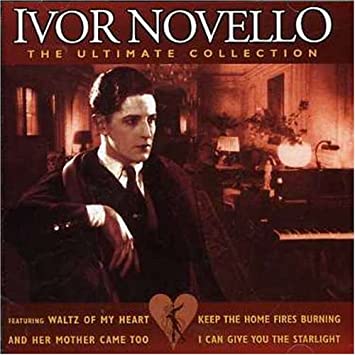

His first big hit was Keep the Home Fires Burning (1914), which was enormously popular during the First World War. His 1917 show, Theodore & Co, was a wartime hit.

After the war, Novello contributed numbers to several successful musical comedies and was eventually commissioned to write the scores of complete shows. He wrote his musicals in the style of operetta and often composed his music to the libretti of Christopher Hassall.

In the 1920s, he turned to acting, first in British films and then on stage, with considerable success in both. He starred in two silent films directed by Alfred Hitchcock, The Lodger and Downhill (both 1927).

On stage, he played the title character in the first London production of Liliom in 1926. Novello briefly went to Hollywood, but he soon returned to Britain, where he had more successes, especially on stage, appearing in his own lavish West End productions of musicals. The best known of these were Glamorous Night and The Dancing Years during the late 1930s.

From that point, he often performed with Zena Dare, writing parts for her in his works. He continued to write for film, but he had his biggest late successes with stage musicals: Perchance to Dream (1945), King’s Rhapsody (1949) and Gay’s the Word (1951). The Ivor Novello Awards were named after him in 1955.

Novello’s mother set up as voice teacher in London, where he met leading performers, including members of George Edwardes’s Gaiety Theatre company, classical musicians such as Landon Ronald, and singers such as Adelina Patti. Another of his mother’s associates was Clara Butt, who taught him to sing Abide with Me when he was a boy of six.

Novello was educated privately in Cardiff and then in Gloucester, where he studied harmony and counterpoint with Herbert Brewer, the cathedral organist. From there, he won a scholarship to Magdalen College School in Oxford, where he was a solo treble in the college choir.

Novello, from his early youth, showed a facility for writing songs, and when he was only 15, one of his songs was published. After leaving school, he gave piano lessons in Cardiff, and then moved to London in 1913 with his mother. They took a flat above the Strand Theatre, which became his London home for the rest of his life.

In London, he found a mentor in Sir Edward Marsh, a well-known patron of the arts and Churchill’s secretary. Marsh encouraged him to compose and introduced him to people who could help his career. He adopted his mother’s middle name, ‘Novello’, as his professional surname, although he did not change it legally until 1927.

In 1914, at the start of the First World War, Novello wrote Keep the Home Fires Burning, a song that expressed the feelings of innumerable families set apart by World War I. Novello composed the music for the song to a lyric by the American Lena Guilbert Ford, and it became a huge success, bringing Novello money and fame at the age of 21.

In other respects, the war had less impact on Novello than on many young men of his age. He avoided enlistment until June 1916, when he reported to a Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) training depot as a probationary flight sub-lieutenant. After twice crashing an aeroplane, Marsh arranged his move to the Admiralty office in central London for the rest of the war.

Novello continued to write songs while serving in the RNAS. He had his first stage success with Theodore & Co in 1916, a production by George Grossmith Jr and Edward Laurillard, with a score composed by Novello and the young Jerome Kern. In the same year, Novello contributed to André Charlot’s revue See-Saw.

In 1917, he wrote for another Grossmith and Laurillard production, the operetta Arlette, for which he contributed additional numbers to an existing French score by Jane Vieu and Guy le Feuvre. In the same year, Marsh introduced him to the actor Bobbie Andrews, who would become Novello’s life partner.

Andrews introduced Novello to the young Noël Coward. Coward, six years Novello’s junior, was deeply envious of Novello’s effortless glamour. He wrote: “I just felt suddenly conscious of the long way I had to go before I could break into the magic atmosphere in which he moved and breathed with such nonchalance”.

In 1918 and after the war, Novello continued to write successfully for musical comedy and revue. The former included Who’s Hooper?, an adaptation of a Pinero play, with a book by Fred Thompson, lyrics by Clifford Grey, and music by Howard Talbot and Novello, and The Golden Moth by Thompson and PG Wodehouse, for which Novello provided the entire score.

For Charlot, he contributed numbers to the revues Tabs, A to Z and Puppets. For the second of these, his songs included one of his few well-known comedy numbers, And Her Mother Came Too, with lyrics by Dion Titheradge, written for Jack Buchanan.

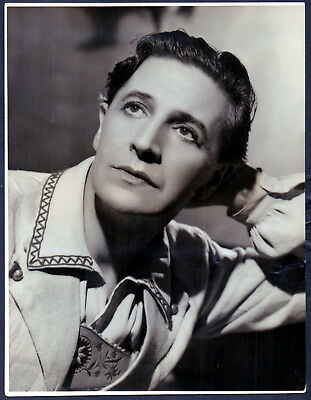

At the same time as his successes as a composer, Novello was making a career as an actor. With what was described as “a classic profile that gained him matinee idol status amongst the film-going public”, he was sought out, on the strength of a publicity photograph, by the Swiss film director Louis Mercanton.

Mercanton offered him a silent-film role as the romantic lead in The Call of the Blood (1920). In the same year, he made another film for Mercanton, Miarka. Novello made his first British film, Carnival, the following year.

Novello made his stage debut in 1921 in Deburau by Sacha Guitry, and, among other stage engagements in the next years, he played Bingley in a charity adaptation of Pride and Prejudice.

At about this time, Novello had an affair with the writer Siegfried Sassoon; it was short-lived, but in the words of Sassoon’s biographer John Stuart Roberts, Novello “was a consummate flirt who collected lovers as he gathered lilacs”.

In 1923, Novello made his American movie debut in DW Griffith’s The White Rose. The same year, he starred in The Man Without Desire, among other British films. He next co-wrote, produced and starred in the successful 1924 play The Rat. The play was made into a film in 1925, which was so successful that two sequels followed in 1926 and 1928. His dramatic roles in the West End included the title character in the first London production of Ferenc Molnár’s Liliom.

Other films in which Novello starred included Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lodger, where he played the title character, and Downhill (both in 1927).

The British film company Gainsborough Pictures offered Novello a lucrative contract, which enabled him to buy a country house in Littlewick Green, near Maidenhead. He renamed the property Redroofs, and he entertained there famously and with little regard for convention. Cecil Beaton, noting the frequent homosexual excesses, coined the phrase, “the Ivor–Noel naughty set”.

Coward had by now caught Novello up professionally, despite a joint disaster when Novello starred in Coward’s play Sirocco in 1927, which closed within a month of opening. In 1928, Novello starred in the silent adaptation of Coward’s much more successful The Vortex, and made his last silent film, A South Sea Bubble. During the late 1920s, Novello was the most popular male British film star and was often dubbed as Britain’s “handsomest screen actor”.

Novello returned to composing for the lyric stage in 1929, writing eight numbers for the revue The House that Jack Built. In the same year, he presented his own play Symphony in Two Flats, which he took to New York the following year. It was followed by a successful Broadway production of his The Truth Game, which brought him to the attention of Hollywood studios. He accepted a contract to write for and appear in MGM films.

He found little to do in Hollywood, however, beyond writing the dialogue for Tarzan the Ape Man. Returning to London, he starred in the sound remake of The Lodger (1932).

After beginning the 1930s with a series of non-musical plays: I Lived with You, Fresh Fields, Proscenium, Sunshine Sisters, Flies in the Sun and Murder in Mayfair, Novello returned to composition in 1935 with Glamorous Night, which was the first of a series of enormously popular musicals.

For all his four 1930s musicals, Novello wrote the book and music, Christopher Hassall wrote the lyrics, and the orchestrations were by Charles Prentice. Glamorous Night starred Novello and Mary Ellis, with a cast including Zena Dare, Olive Gilbert and Elizabeth Welch, and ran from May 1935 to July 1936, at Drury Lane and then the London Coliseum.

Careless Rapture ran from September 1936 for 296 performances, with Novello, Dorothy Dickson and Zena Dare in the leading roles. Crest of the Wave starred Novello, Dickson and Gilbert, and ran from September 1937 for 203 performances. The last of Novello’s pre-war musicals was The Dancing Years, which starred Novello, Ellis and Gilbert, opened at Drury Lane, closed on the outbreak of the Second World War, and reopened at the Adelphi Theatre, running for a combined total of 696 performances, closing on July 8, 1944.

Novello presented only two new shows during the Second World War. Arc de Triomphe, a musical vehicle for Mary Ellis, was only a modest success, but Perchance to Dream was immensely successful, running for 1,022 performances.

In between the two shows, Novello had been in serious legal trouble and served four weeks in prison for misuse of petrol coupons, a serious offence under rationing laws in wartime Britain. An admiring fan had stolen the coupons from her employer, but the court found that Novello was also culpable. The prison term, though short, came as a severe shock to Novello, both mentally and physically, and had serious lasting effects.

Not everybody was supportive; Coward’s sympathy was limited: “He’s been fighting like a steer to keep going as before the war and hasn’t done a thing for the general effort”, but when Novello returned to The Dancing Years after his release, he received a rapturous ovation on his first entrance.

Novello’s last full-scale production in this style, King’s Rhapsody, was described as “a self-consciously romantic counter-blast to the modern musical: crown princes, ballrooms, royal yachts, beautiful princesses and a full-scale coronation”.

After the rigours of war, this escapist entertainment had strong box-office appeal, and ran for 841 performances. The show starred Novello, and the cast included Phyllis Dare, Zena Dare, Olive Gilbert and Bobbie Andrews. It was still running, at the Palace Theatre, when Novello’s last show opened in 1951. This was Gay’s the Word.

Novello had written no role for himself; the show starred the comedy actress Cicely Courtneidge and was a departure from his established pattern, balancing the contrasting styles of European operetta and post-war American musicals. A reviewer from The Times commented that the show “cheerfully parodied the very Ruritanian romances to which he owed his most triumphant successes”.

Novello died suddenly on March 6, 1951, from a coronary thrombosis at the age of 58, a few hours after completing a performance in the run of King’s Rhapsody. He was cremated at the Golders Green Crematorium, and his ashes were buried beneath a lilac bush and marked with a plaque that reads ‘Ivor Novello 6th March 1951 ‘Till you are home once more’.

Only a few weeks before Novello’s death, Coward had written of him: “Theatre – good, bad and indifferent – is the love of his life. For him, other human endeavours are mere shadows … The reward of his work lies in the indisputable fact that whenever and wherever he appears the vast majority of the British public flock to see him.”

Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians writes of Novello that he was “until the advent of Andrew Lloyd Webber, the 20th Century’s most consistently successful composer of British musicals”.

The Ivor Novello Awards for songwriting, established in 1955 in Novello’s memory, are awarded each year by the The Ivors Academy (formerly the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors) to British songwriters and composers as well as to an outstanding international music writer.

Among the many winners of Ivor Novello Awards, since 1955, are: Amy Winehouse, Robbie Williams, Midge Ure, Sting, Cat Stevens, Rod Stewart, Ed Sheeran, Neil Sedaka, John Rutter, Smokey Robinson, Tim Rice, Ozzy Osbourne, Gary Numan, Anthony Newley, George Michael, Freddie Mercury, Paul McCartney, Madonna, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Annie Lennox, John Lennon, Avril Lavigne, Beyonce, Mark Knopfler, Elton John, Mick Jagger, George Harrison, The Gibbs Brothers (Barry, Maurice Robin: The Bee Gees), Bob Geldof, Noel Gallagher, Duffy, Phil Collins, Eric Clapton, Kate Bush, David Bowie, James Dean Bradfield, James Blunt, Gary Barlow, Adam Ant, Lily Allen, Adele and Bryan Adams.

A scholarship in memory of Novello was established at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, and in 1952 a bronze bust of him by Clemence Dane was unveiled at Drury Lane. In St Paul’s, Covent Garden, known as the actors’ church, a panel was installed to commemorate Novello, and in 1972, to mark the 21st anniversary of his death, a memorial stone was unveiled in St Paul’s Cathedral.

In 1993, the centenary of Novello’s birth was marked by several celebratory shows around the UK, including one at the Players Theatre in London. In 2005, the Strand Theatre, above which Novello lived for many years, was renamed the Novello Theatre, with a plaque in his honour set at the entrance.

On June 27, 2009, a statue of Novello was unveiled outside the Wales Millennium Centre in Cardiff Bay. Plaques detailing some of his best-known songs are fitted to the pedestal, along with a dedication to Novello.

Novello’s memory is promoted by The Ivor Novello Appreciation Bureau, which holds annual events around Britain, including an annual pilgrimage to Redroofs each June. Redroofs was sold after Novello’s death and is now a theatre training school.

Novello was portrayed in Robert Altman’s 2001 film Gosford Park by Jeremy Northam, and several of his songs were used for the film’s soundtrack, including Waltz of My Heart, And Her Mother Came Too, I Can Give You the Starlight, What a Duke Should Be, Why Isn’t It You? and The Land of Might-Have-Been.

In Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians, the author writes that although Novello’s oeuvre is generally thought of as “romantic” and “Ruritanian”, his music “was far more varied than his current reputation suggests”. It contends that such romantic hits as Some Day My Heart Will Awake were balanced by “rousing operetta choruses … and jazz age numbers” while “Rose of England is a stately patriotic piece that stands comparison with Elgar or Walton”.

BACK TO HOME PAGE