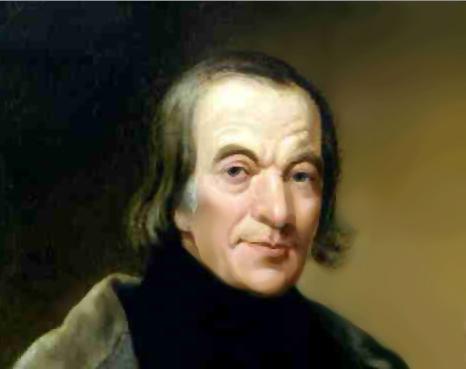

Robert Owen

NEWTOWN-BORN Robert Owen was a Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist and social reformer, and a founder of Utopian socialism and the cooperative movement. An advocate of the working class, he strove to improve factory working conditions, promoted experimental Utopian communities, and sought a more collective approach to child rearing, including government control of education.

The son of a saddler, ironmonger, and local postmaster, Owen was born 250 years ago, on May 14, 1771, in the small mid Wales market town of Newtown, brought up a Welsh-speaker with a proud Welsh heritage. His mother was the daughter of a local farming family near the banks of the River Severn.

His then home county of Montgomeryshire bore little resemblance to today’s modern unitary authority of Powys. As one recent article on Owen’s life stated: “…life expectancy was on average 36 years, few had the vote, the USA was still a British colony, while Beethoven and Napoleon were still in nappies.”

After leaving school at the age of 10 to be apprenticed to a Stamford, Lincolnshire, draper for four years, he went on to gain wealth in the early 1800s from a textile mill at New Lanark, Scotland. He worked in London before relocating to Manchester in his late teens.

In 1824, he moved to America and put most of his fortune in an experimental socialistic community at New Harmony, Indiana, as a preliminary for his Utopian society. It lasted about two years. Other Owenite communities also failed, and in 1828 Owen returned to London, where he continued to champion the working class, lead in developing cooperatives and the trade union movement, while supporting child labour legislation and free co-educational schools.

David Smith and Chris Hall, of Co-ops & Mutuals Wales, in a 2021 joint article in The National, describe Owen as “a political giant” whose worldwide reputation has not always been reflected in his home country.

“There is no question about his Welshness,” they wrote. “But is he a political icon? Currently, from a Welsh perspective, probably not. Very few ordinary citizens of Wales have heard of him. But this is an unfortunate reflection on those who write Welsh history and educational curricula. From a global perspective, Owen is a political giant.”

In Scotland, Owen met David Dale, philanthropist and proprietor of the New Lanark Mills near Glasgow and later married his daughter Caroline Ann. Subsequently, Owen and his business partners bought the New Lanark mills, where he became the manager of Britain’s largest and best equipped cotton mills aged just 29.

There, Owen began building upon Dale’s successful ideas and made his enlightened vision a reality. ‘Model’ housing at low rents, an employee sickness and pension fund, free medical services, free infant, school provision without fear of punishment, a refusal to employ children under 10 years of age and free adult education. These were offered alongside a not-for-profit store, bank, hall, church, and chapel facilities in Owen’s community.

Owen’s platform for national intervention was based upon his 1813 publication, A New View of Society, which was a combination of ideas surrounding economic success and social reform he had engineered at New Lanark.

But Owen rarely had the same degree of control in using his considerable fortune to extend the New Lanark model as he went on to engineer the new model co-operative community of New Harmony in Indiana.

On his return to England in 1829, Owen found that his ideas for a revolutionary reform of Britain’s economic and social order were now being taken up among the working class. It was a new experience to be regarded by them as a pioneer. In this he provided something indispensable to the emergence of an organised working-class movement.

During this period, co-operative ideals were being crystallised and began to emerge as a future movement; with an appeal to the working class which pointed to working-class power in the 19th Century and a significant counter to rapacious capitalism.

Owen strongly condemned existing methods of education, where children were made to memorise instead of learning to understand and be creative. The real purpose of education was the formation of good character, and this was central to his philosophy.

In 1816, he opened an Institute for the Formation of Character, a school for five to 12 year-olds, properly equipped with visual aids and a teacher/pupil ratio of 1 to 18. Pupils were taught not just reading, writing and arithmetic, but also botany, geology, geography, science, and history.

They were taken on field trips, enjoyed music and dance and, unlike most schools of the time, including public schools, his was not reliant on corporal punishment for discipline.

Owen’s approach was that working-class children deserved the same chances as others and that people’s lives extended beyond the factory.

Previously unthinkable, Owen’s ideas transfer well to our modern society, where education, universal suffrage, the modern welfare state and enjoying material comfort are standard.

Owen’s contribution to education is relevant today in demonstrating a relationship between education, work, and society, as a mechanism of social change. Certainly, his view that man was shaped by the environment was no less than revolutionary.

Owen’s ideas led to co-operatives, mutuals, credit unions, trade unions, building and friendly societies, economic community development and much more. He is often referred to as the ‘father’ of the worldwide co-operative movement.

Owen’s agitation for social change, along with the work of ‘Owenite’ supporters and of his own children, helped to bring lasting social reforms in women’s and workers’ rights, establish free public libraries and museums, child care and public, co-educational schools, and pre-Marxian communism, and develop the Co-operative and trade union movements.

Owen’s legacy of public service continued with his four sons, Robert Dale, William, David Dale, and Richard Dale, and his daughter, Jane, who followed him to America to live at New Harmony.

Smith and Hall call in their joint article for Owen’s profile to be raised in Wales: “What other Welsh political icon could claim to have such profound and wide-ranging influence and impact than Robert Owen?

“Would the creation of an annual Robert Owen Day spur us to action in creating a co-operative education system for the co-operative Wales we wish it to be? It would certainly be a step in the right direction.”

Although he had spent most of his life in England and Scotland, Owen returned to his native town of Newtown towards the end of his life. He died there on November 17, 1858 and the Co-operative Movement later erected a monument to Owen at his burial site.

A bust of Owen by Welsh sculptor Sir William Goscombe John was donated to the International Labour Office library in Geneva, Switzerland.

Owen the reformer, philanthropist, community builder and spiritualist spent his life seeking to improve the lives of others. In these reforms he was ahead of his time.

Back to HOME PAGE