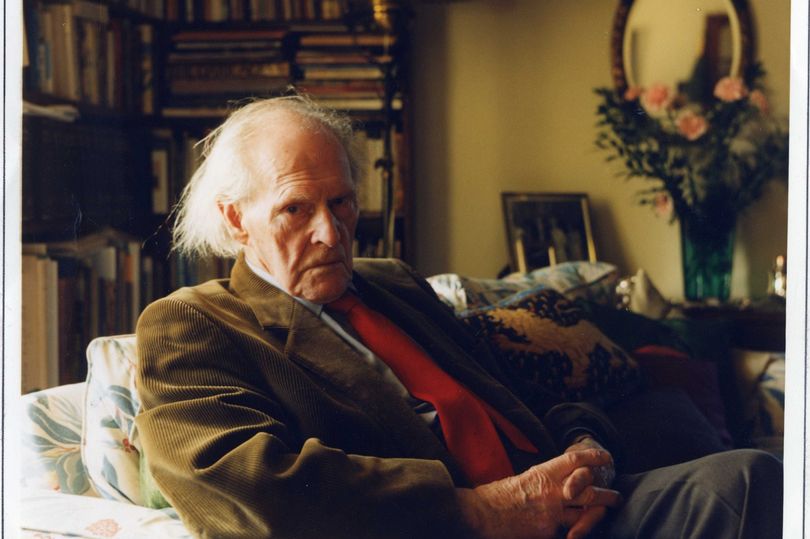

RS Thomas

RS THOMAS was a poet and priest noted for his nationalism, spirituality and dislike of the anglicisation of Wales. His lucid, austere verse expressed an undeviating affirmation of the values of the common man.

Ronald Stuart Thomas was born in Cardiff on March 29, 1913. The family moved to Holyhead in 1918 because of his father’s work in the Merchant Navy. Thomas grew up in an English-speaking household, only learning Welsh when he was 30, a major cause of regret as he didn’t feel fluent enough to write poetry in his native tongue.

He was awarded a bursary in 1932 to study at the University College of North Wales, Bangor, where he studied Classics. In 1936, after he completed his theological training at St Michael’s College, Llandaff, he was ordained as a priest in the Anglican Church in Wales.

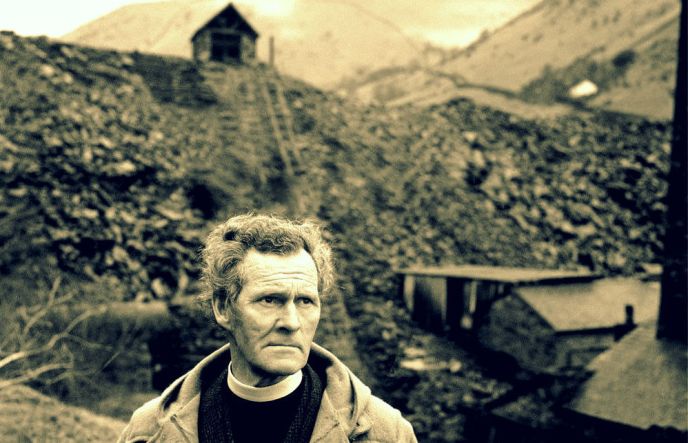

From then until his retirement in 1978 Thomas’s ministry took him to a number of rural parishes in north Wales: the bleak beauty of the landscape and the hard lives of the peasant farmers became abiding themes in his poems.

In his first post in Y Waun, Denbighshire, he met his future wife Mildred (Elsi) Eldridge who was an English artist. They had one son, Gwydion, born in 1945.

He subsequently became curate-in charge of Tallarn Green, Flintshire, and from 1942 to 1954 Thomas was rector of St Michael’s Church, Manafon, near Welshpool in rural Montgomeryshire. It was during his time there that he began to study Welsh and that he published his first three volumes of poetry, The Stones of the Field (1946), An Acre of Land (1952) and The Minister (1953).

Thomas’s poetry achieved a breakthrough with the publication in 1955 of his fourth book, Song at the Year’s Turning, in effect a collected edition of his first three volumes. This was critically very well received and opened with Betjeman’s famous introduction. His position was also helped by winning the Royal Society of Literature’s Heinemann Award.

The 1960s saw him working in a predominantly Welsh-speaking community and he later wrote two prose works in Welsh, Neb (Nobody), an ironic and revealing autobiography written in the third person, and Blwyddyn yn Llŷn (A Year in Llŷn). In 1964 he won the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry. From 1967 to 1978 he was vicar of St Hywyn’s Church (built 1137) in Aberdaron at the western tip of the Llŷn Peninsula. Thomas retired as a clergyman in 1978.

Free from church constraints, he was able to become more political and active in campaigns that were important to him, becoming a fierce advocate of Welsh nationalism.

A Welsh Testament speaks in contemptuous tones to those English tourists who want to turn his country into a “museum”. However, he is also resentful of the limitations of a life lived with “the absurd label/of birth, of race hanging askew/About my shoulders.”

Though an ardent Welsh nationalist, Thomas learned to speak Welsh only in his 30s and did not feel comfortable writing poetry in that tongue; however, Neb (No One), a collection of autobiographical essays, was written in Welsh.

His early poems, most notably those found in Stones of the Field (1946) and Song at the Year’s Turning: Poems 1942–1954 (1955), contained a harshly critical but increasingly compassionate view of the Welsh people and their stark homeland.

In Thomas’s later volumes, starting with Poetry for Supper (1958), the subjects of his poetry remained the same, yet his questions became more specific, his irony more bitter, and his compassion deeper. In such later works as The Way of It (1977), Frequencies (1978), Between Here and Now (1981) and Later Poems 1972–1982 (1983), Thomas described with mournful derision the cultural decay affecting his parishioners, his country, and the modern world.

Thomas wrote over 1,500 poems in his life and although there were developments in subject and style – from the early poems rooted in the physical realities of place to the more abstract and metaphysical investigations of his later work – his poetry was consistent in its seriousness of purpose. In Thomas’s eyes the modern world with its technological conveniences was a dangerous distraction from our spiritual existence.

Two of Thomas’s later collections, Mass for Hard Times and No Truce with the Furies, published in 1993 and 1995, respectively, reveal the hard edge, spiritual questioning, and cultural skepticism of his later poetry.

The long-awaited Collected Poems, 1945-1990 was published in 1993 to coincide with Thomas’s 80th birthday. In a Times Literary Supplement review of the volume, Stephen Knight observes: “From the beginning, Thomas was determined to follow his own path and this extraordinary book bears witness to that.”

Thomas’s uncompromising vision continued to attract admiration: in 1964 he won the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry and in 1996 was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. He received the prestigious 1996 Lannan Literary Achievement Award for Lifetime Achievement.

Thomas died at his home in Pentrefelin, near Criccieth, on September 25, 2000, survived by his second wife, Elizabeth Vernon, after suffering heart trouble at the age of 87. A memorial event celebrating his life and poetry was held at Westminster Abbey. Thomas’s ashes are buried near the door of St John’s Church, Porthmadog, Gwynedd.

Although a poet who hardly ever left the narrow confines of north Wales, at his death he was hailed as a major European poet.

M Wynn Thomas said: “He was the Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn of Wales because he was such a troubler of the Welsh conscience. He was one of the major English language and European poets of the 20th Century.”

Recognized as one of the leading poets of modern Wales, Thomas writes about the people of his country in a style that some critics have compared to the nation’s harsh and rugged terrain.

Using few of the common poetic devices, Thomas’s work exhibits what Alan Brownjohn of the New Statesman calls a “cold, telling purity of language.”

James F Knapp of Twentieth Century Literature explains that “the poetic world which emerges from the verse of RS Thomas is a world of lonely Welsh farms and of the farmers who endure the harshness of their hill country. The vision is realistic and merciless.

Thomas viewed western (specifically English) materialism and greed, represented in the poetry by his mythical ‘Machine’, as the destroyers of community. He could tolerate neither the English, who bought up Wales and in his view stripped it of its wild and essential nature, nor the Welsh whom he saw as all too eager to kowtow to English money and influence.

Thomas was an ardent supporter of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and described himself as a pacifist, but also supported the terrorist Meibion Glyndŵr fire bombings of English-owned holiday cottages in rural Wales. On this subject he said in 1998, “What is one death against the death of the whole Welsh nation?”

Almost all of Thomas’s work concerns the Welsh landscape and the Welsh people, themes with both political and spiritual subtext. His views on the position of the Welsh people, as a conquered people are never far below the surface. As a cleric, his religious views are also present in his works.

His earlier works focus on the personal stories of his parishioners, the farm labourers and working men and their wives, challenging the cosy view of the traditional pastoral poem with harsh and vivid descriptions of rural lives. The beauty of the landscape, although ever-present, is never suggested as a compensation for the low pay or monotonous conditions of farm work. This direct view of “country life” comes as a challenge to many English writers writing on similar subjects and challenging the more pastoral works of contemporary poets such as Dylan Thomas.

Thomas’s later works were of a more metaphysical nature, more experimental in their style and focusing more overtly on his spirituality.

Despite his nationalism Thomas could be hard on his fellow countrymen. Often his works read more as a criticism of Welshness than a celebration. Al Alvarez said, “He was wonderful, very pure, very bitter, but the bitterness was beautifully and very sparely rendered. He was completely authoritative, a very, very fine poet, completely off on his own, out of the loop but a real individual. It’s not about being a major or minor poet. It’s about getting a work absolutely right by your own standards and he did that wonderfully well.”

Robert Hass, writing in the Washington Post, noted that Thomas “has made remarkable poetry out of the flinty and unforgiving hill country of Wales and an obdurate, existential Christianity.”

In Neb: Golygwyd gan Gwenno Hywyn, an autobiography, Thomas speaks of his tendency to “look back and see the past as better,” according to Gwyneth Lewis in London Magazine. On several occasions he has expressed his dismay at the industrialization of Wales, arguing that the country’s natural beauty has been ruined.

Despite what he sees as his own “small talent,” Thomas is often ranked among the most important Welsh poets of the past century. Writing in the Anglo-Welsh Review, R George Thomas found him to be “the finest living Welsh poet writing in English.”

Thomas himself would say only, “My chief aim is to make a poem. You make it for yourself firstly, and then if other people want to join in then there we are.”

A Welsh Testament

All right, I was Welsh. Does it matter?

I spoke a tongue that was passed on

To me in the place I happened to be,

A place huddled between grey walls

Of cloud for at least half the year.

My word for heaven was not yours.

The word for hell had a sharp edge

Put on it by the hand of the wind

Honing, honing with a shrill sound

Day and night. Nothing that Glyn Dwr

Knew was armour against the rain’s

Missiles. What was descent from him?

Even God had a Welsh name:

He spoke to him in the old language;

He was to have a peculiar care

For the Welsh people. History showed us

He was too big to be nailed to the wall

Of a stone chapel, yet still we crammed him

Between the boards of a black book.

Yet men sought us despite this.

My high cheek-bones, my length of skull

Drew them as to a rare portrait

By a dead master. I saw them stare

From their long cars, as I passed knee-deep

In ewes and wethers. I saw them stand

By the thorn hedges, watching me string

The far flocks on a shrill whistle.

And always there was their eyes; strong

Pressure on me: You are Welsh, they said;

Speak to us so; keep your fields free

Of the smell of petrol, the loud roar

Of hot tractors; we must have peace

And quietness.

Is a museum

Peace? I asked. Am I the keeper

Of the heart’s relics, blowing the dust

In my own eyes? I am a man;

I never wanted the drab role

Life assigned me, an actor playing

To the past’s audience upon a stage

Of earth and stone; the absurd label

Of birth, of race hanging askew

About my shoulders. I was in prison

Until you came; your voice was a key

Turning in the enormous lock

Of hopelessness. Did the door open

To let me out or yourselves in?

Sources include Britannica, Poetry Archive, Poetry Foundation

BACK TO HOME PAGE